The next twenty years in aviation will define what commercial aircraft — and their cabins — look like for the next century. What looks futuristic to us now will be commonplace in the future: the reshaped tube-with-wings that are two of the Airbus ZeroE hydrogen-powered concepts, the more radically different blended wing body, or the entirely new range of air taxis, personal air vehicles, urban/regional mobility aircraft and so on.

The next twenty years in aviation will define what commercial aircraft — and their cabins — look like for the next century. What looks futuristic to us now will be commonplace in the future: the reshaped tube-with-wings that are two of the Airbus ZeroE hydrogen-powered concepts, the more radically different blended wing body, or the entirely new range of air taxis, personal air vehicles, urban/regional mobility aircraft and so on.

Decarbonising passenger aviation and developing these entirely new markets for air travel and connectivity is exciting, and it’s an enormous opportunity for aviation. But with this excitement and opportunity comes a serious question: for whom are these aircraft designed?

Let’s look at the cabin of the world’s most-produced aircraft, the Boeing 737. The 737 is nearly 60 years old, and some of the oldest examples still flying date back to the early 1970s, nearly 50 years ago. It seems entirely likely that today’s newly sold 737 MAX aircraft may still be flying for 30 or even 40 more years in some capacity, somewhere in the world. The new aircraft produced in the 2030s or 2040s — in other words, those being designed today — could potentially have derivatives and aircraft family members operational in 2100.

Winding the clock back, the shape of the 737’s fuselage is even older than that, of course: it is the same as that of the Boeing 707, studies for which began in the 1940s and first flew — as the Boeing 367-80 — in 1954.

And the 737’s seat sizing feels like it dates back almost 70 years. Delta Air Lines cites its 737-900ER seat width at 16.3-17.3”. So does United, although it says the MAX 8 seats are 16.6-17.8”. American gives the same numbers for the MAX (and for its 737-800 “version 2”, which one presumes is its controversial “Oasis” layout), but for its “version 1” of the 737-800 it cites 15.9-17.3”.

The Airbus A320, of course, has a slightly wider cabin, allowing airlines either to install seats roughly an inch wider or to add a wider aisle to allow for faster boarding and disembarkation. The A220, né Bombardier C Series, has so far been delivered with the wider 2-3 seat layout.

Widebodies vary more — Airbus and Boeing offer choices of density on the 777 and A350 — but both manufacturers allow airlines to choose seats of 17” and narrower.

That’s simply too small for today’s passenger, let alone the passenger of twenty, forty or sixty years from now.

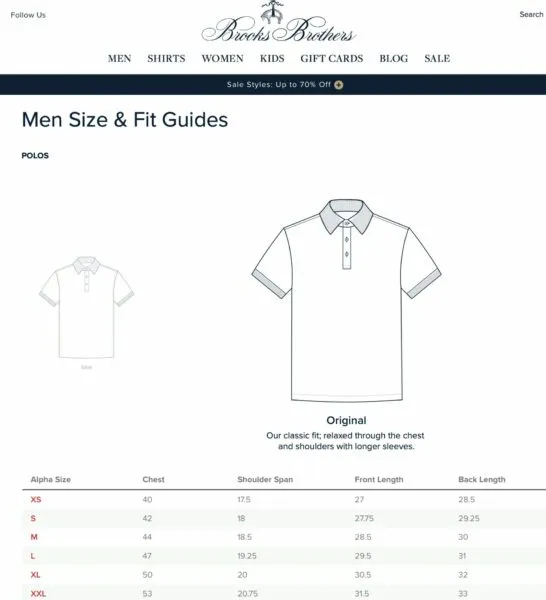

For a reality check, let’s take a look at the sizing guide for men’s clothing from the well-known US retailer Brooks Brothers, taking the original fit sizing for casual polo shirts.

A 17” seat doesn’t even meet the shoulder span for an extra-small (XS) sizing, which gives a shoulder of 17.5”. A medium is 18.5” — and look around the aircraft the next time you fly, or your market or supermarket, and ask yourself how many of the people you see might be wearing a medium shirt compared with a large or extra-large.

It’s not just Brooks Brothers either.

Even 21 years ago in the year 2000, NASA’s anthropometric dimensional data for the American male (the snappily named Figure 3.3.1.3-1, 2 of 12) suggest that the breadth of a 50th percentile (measured as forearm-forearm, giving a slightly greater span than the shoulder) is 21.7”.

People in the 5th percentile — that’s the slightest 5% of people — are at 19.2”. The 95th percentile, meanwhile, is at 24.2”. Design principles usually call for designing for the 5th to 95th percentile.

How many economy class seats fit into that 19.2–24.2 range? Your author would suggest precisely zero.

Indeed, it would not be surprising to see quite a few premium economy and business class seats fail that test as well. And what of the dimensional data for 2020, or even that projected for 2040 or 2060?

There’s an opportunity, as aircraft designers create the first of the hydrogen airliners, and the wide variety of newer market air mobility vehicles, to design to standards that will reasonably fit the 5th-95th percentile of people, or even more. Aviation should live up to that opportunity.

Related Articles:

- Study shines light on optimum aircraft seat dimensions

- Wider seats, wider aircraft: a paradigm shift for aviation?

- Those confusing aircraft seat measurements explained

- What passenger experience future for Airbus hydrogen aircraft?

- More room in economy? Differentiation debate resurfaces

- Larger crash test dummies will better reflect passenger size

- PaxEx Podcast: Flyers Rights makes the case for seat size standards

Featured image credited to Mary Kirby