With unruly passenger incidents on the rise, it is timely to ask what role cabin conditions might play in passenger behavior.

With unruly passenger incidents on the rise, it is timely to ask what role cabin conditions might play in passenger behavior.

A recent in-depth study of seat pitch and width, prepared as a doctoral dissertation by TUI Delft student Shabila Anjani, includes feedback from participants on the feelings of stress they experience in various seating configurations, allowing an examination of the level of stress induced by cabin design alone.

The study included over 300 volunteer participants of different sizes sitting in simulated cabin conditions to determine the comfort and discomfort levels of a combination of seat pitch and seat width.

The study, on its own, is interesting from a designer’s perspective. It shows that an additional inch of width in the seat — from 17” to 18”— can have a more positive impact on passenger comfort than increasing seat pitch (the distance from any point on one seat to the exact same point on the seat in front or behind it.)

As Anjani explains in her dissertation: “It was determined that given the same amount of additional floor area, widening the seat is more effective on comfort than increasing the pitch.”

Airlines must balance offering passenger comfort and getting the optimal utility from their aircraft asset to provide passengers with the low fares they crave. But keeping a 30” pitch while increasing seat width from 17” to 18” would result in a similar boost to passenger comfort as offering a 17”-wide seat with a seat pitch of 34”, the study finds.

While Anjani’s detailed findings on various comfort factors will interest industry designers and airline executives responsible for cabin planning, this writer would argue that the characteristics of discomfort deserve a closer look.

It’s essential to keep in mind that people react differently to stressors, and not everyone who feels highly stressed will necessarily become violent or uncooperative onboard. Still, life and travel stressors combined with cabin stressors might push some over the edge.

The study participants had no travel stressors affecting their responses to the surveys — they were not leaving family behind, had not gone through airport screening, and had no concerns about making a tight connection. Their responses were isolated from these other factors and could only reflect the impact of the cabin design. Yet, the discomfort and stress levels reported during the short period they participated in the study were significant.

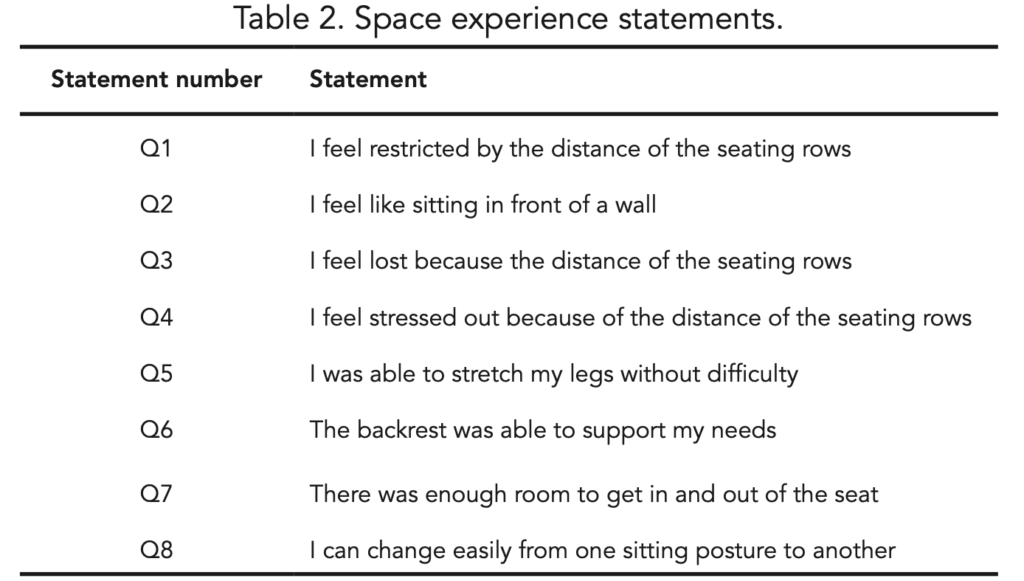

The first four “space experience statements” used in the study’s questionnaire — Q1 to Q4 — reflect some level of stress or stress-inducing conditions. Q1: I feel restricted; Q2: I feel like sitting in front of a wall; Q3: I feel lost because the distance of the seating rows; Q4: I feel stressed out because the distance of the seating rows.

When seated at a 28″ pitch, the mean responses showed high responses to Q1 (6.92), Q2 (6.5), and Q4 (5.52). Those responses dropped significantly when seated at a 30” pitch: Q1 (4.57), Q2 (4.49), and Q4 (3.68). Adding more inches to the pitch beyond 30” did not reduce stressful discomfort at the same rate, though a 34″ pitch registered the lowest levels of stressful discomfort.

In terms of seat width, the study examined participants’ feeling of comfort when sitting in 17″- and 18″-wide seats. While respondents answered high (7.04) to the psychological comfort statement that their 17″ seat was “wide enough for my body to fit”, they still reported significant levels of restriction regarding the distance between armrests, and the closeness of their seatmate.

So, crucially, the feeling of being restricted is not limited to whether or not the body fits in the aircraft seat.

All discomfort and stress sentiments dropped as seat width was increased to 18″. The mean pain-point sensations combined were reduced by 45% when seat width was increased by one inch, from 17” to 18”. The mean pleasure-point sensations increased by 26%. In other words, the pain-point reduction was more significant than the pleasure-point increase, which makes investing in 18”-wide seat width a significant passenger well-being benefit.

Moreover, the replies to Q8 — “the width of the seat makes me relaxed” — earned a high positive sentiment (6.49) even with a 28” width.

As someone who worked in the seating industry for decades and had a healthy skepticism of Airbus’ long-standing assertion that an 18” seat width standard would make a difference in passenger comfort — a notion it espoused even as the airframer developed and sold high-density widebodies — the results are delightfully surprising.

It seems counterintuitive. How could getting an extra inch in seat width compensate for the discomfort of restricted legroom?

It is a question, which as Anjani’s dissertation states, warrants further study. However, in her dissertation, she compares her results with other studies conducted in 2020, which seem to prove the theory that an 18” wide seat with 30” pitch yields roughly the same increase in comfort results as a 17” wide seat with 34” pitch.

It reduces discomfort enough to suggest that an 18” seat width and 30” pitch should be a minimum standard of cabin seating dimensions.

While regulators, especially the FAA, have been reluctant to regulate seat width and pitch, rising incidents of unruly behavior onboard warrant a reexamination of all factors which may contribute to air rage.

The stress levels reported by study participants on the ground (with no other travel-related stressors contributing to their feelings) suggest that a deeper study of seating dimensions — more focused on stress factors and passenger behavior — might benefit airlines as much as it does passengers.

These findings do not excuse unruly passengers for their disruptive actions. It is simply not enough to say that seating conditions are too cramped. But the industry should examine whether it pays for airlines to fit travel-anxious passengers into their tin cans like so many pressurized sardines or whether giving an inch on seats could help reduce the stress levels all passengers experience.

Related Articles:

- Those confusing aircraft seat measurements explained

- More room in economy? Differentiation debate resurfaces

- Flyers Rights questions FAA evidence for not setting seat standards

- FAA quiet on seat pitch and width data as pressure mounts for standards

- PaxEx Podcast: Flyers Rights makes the case for seat size standards

- Airlines decline to self-regulate on PaxEx, despite threat of new laws