Demand for customization of the airline passenger experience is growing from airlines and from passengers, largely driven by the increasingly customized lives we lead: Spotify playlists just for us, cars that remember our preferred seating positions, Netflix’s “because you added X to your list” recommendations, Amazon’s “customers who bought this item also bought” lists, and so on.

The benefits, particularly for inflight entertainment and seating, are fairly clear. But a key question is how to uniquely identify passengers: their phone or tablet? The airline’s app? A wearable? Their passport or boarding pass? Or biometrics: their retina, iris, fingerprint, facial scanning, or something else? It’s somewhat surprising how many answers remain to this question of what the token will be to recognise each passenger.

As biometric sensors make their way from phones to smartwatches and laptops, the passenger experience industry is looking at how best to introduce this technology to the aircraft cabin for customization purposes. But with numerous challenges and the key issue of “why bother” remaining unresolved, the question is whether biometrics are a red herring or a key part of delivering customization.

A fundamental challenge is what we could call the “Apple Watch” problem: an elegant if hamstrung solution to a series of relatively small pain points that have cheaper and perhaps more obvious solutions. Yes, “continue watching this movie” is nice, but is it crucial, and can we develop another solution like better fast-forwarding or scene selection? Just how much of a pain point is having to recline a business class seat, and what’s the amount of benefit to be gained — especially when airlines have different business class seats and even the same product may be different depending on the type of aircraft, subfleet or even the direction a passenger is facing?

But let’s take the benefits as read and as likely to increase over the years. What’s the token? The most obvious answer is “the smartphone”, but is it the phone itself or a Snapcode-style 2D barcode snapped within the airline’s app? The latter seems the most cross-platform of options, although there are still large airlines without useful, reliable and fully featured apps for the major platforms.

And even though most passengers have a smartphone these days, there needs to be an elegant failback for those travelers whose phones are out of battery: a frequent flyer number, PNR, one-time code on the boarding pass, or a new login. Yet fundamentally, unless the industry picks the right technology, this failback option may end up being more elegant than the technological option.

The next big question is whether passengers trust airlines with their personal information. If you’re flying to a country that criminalises your sexuality, for example, do you want your airline to know what you watched on the plane? Does it depend on the airline? To whom is it visible? Do you always want your kids, parents or colleagues travelling with you to see the “Because you watched X” recommendation on your screen? How secure is that data, and in which country is it held?

Airline IT is infamous for being a series of relatively modern applications kludged together with legacy bespoke systems, so the “is it safe” question is also linked in to “will it work” — and “will it just work”? To be a mainstream passenger answer to the question of identity, this can’t be fiddly: it has to be the inflight equivalent of turning the pain and inconsistent user interface of Bluetooth pairing into Apple’s AirPods open-the-lid-to-pair experience. Yes, it’s a very minor change, but sometimes that’s what’s needed to drive a new technology.

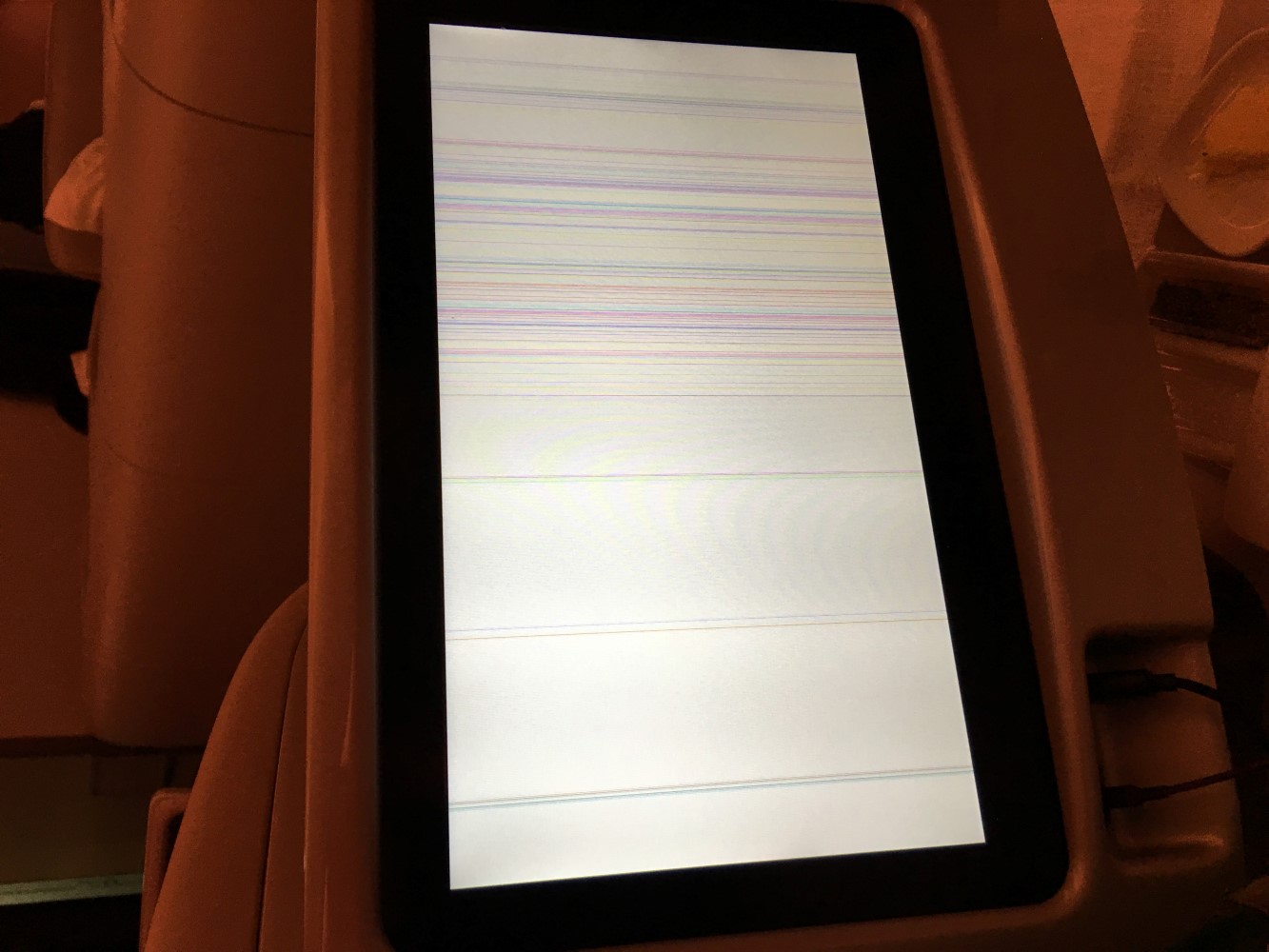

Another issue in technology selection: airlines’ eXport experience. Thousands of airline seats even today offer the round proprietary Panasonic Avionics connector for previous generations of iPod and iPhone that Apple killed in one fell swoop when it moved to the Lightning cable. Lead time and hard product life for seats and IFE is often around four to five times the lifespan of consumer electronics, making airlines often reluctant to pick a horse — especially if the saddlemaker is going to change six months later.

But one of the greatest questions — and the one most likely to resolve the issue — is why airline IT can’t do all this before the passenger gets to the seat. As more information flows on and off the aircraft inflight and on the ground, some airlines are already welcoming customers by name on the IFE monitor. If that’s already possible, it makes the most sense to use this existing capability to drive customization, with a “login as another passenger” option if the system doesn’t get it right.

How does an airline ensure consistency between seats, IFE suppliers and other differences within its fleet? Image: Panasonic

Related Articles: