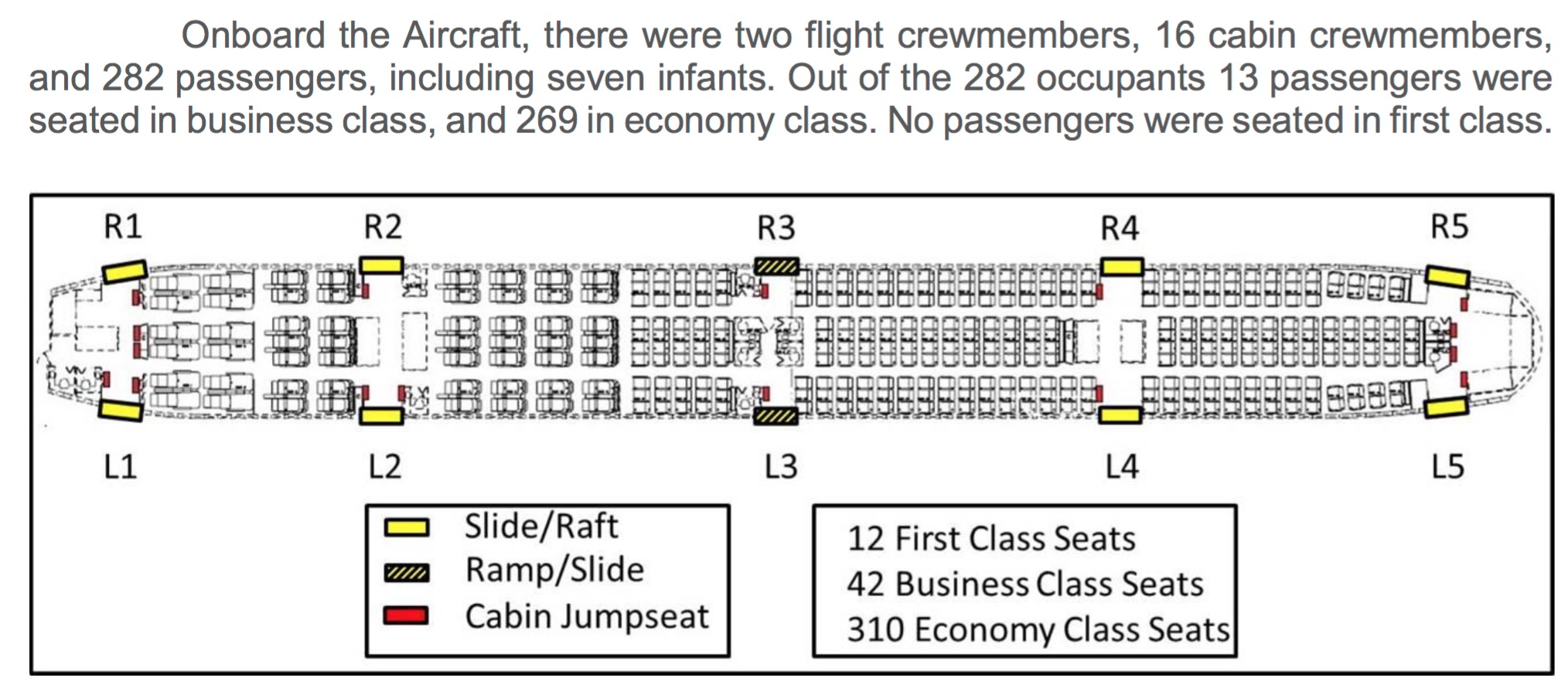

Regardless of the cause of the crash landing of the Boeing 777-300 operating Emirates flight EK521 in Dubai last month, the initial facts of the evacuation presented by the GCAA make sobering reading for anyone concerned with aviation safety. The GCAA’s initial factual report is a model of clarity and precision, and is to be commended.

The most concerning aspect is the failure of the slides to function in relatively high winds, and the resulting requirement for evacuation doors to be blocked from use. Compounding this issue was the need for passengers to be redirected to alternative doors, and adding further complications was the increasingly common reaction by passengers to open overhead bins and retrieve personal effects.

The cabin crewmembers stated that when the aircraft impacted and slid along the runway, passengers started to unfasten their seatbelts and stand up. An announcement was made for the passengers to remain seated. When the aircraft came to rest, some passengers were screaming, grabbing their belongings, and asking the cabin crewmembers to open the doors. The cabin crewmembers followed the operator’s safety instructions that prohibit passengers taking their carry-on baggage during an evacuation, and they instructed the passengers to leave their bags behind. However, several passengers evacuated the aircraft carrying their baggage. Footage of the evacuation showed a number of passengers outside the aircraft with their baggage.

No wonder, perhaps, that the aircraft commander and the lead flight attendant were still searching the cabin until a fuel tank exploded nine minutes after the aircraft came to a stop, forcing them to jump out of a door without a working slide. The issues go beyond previously identified concerns around the sufficiency of non-physical evacuation testing in increasingly dense aircraft cabins. Astoundingly, the GCAA report suggests that zero of the emergency slides functioned fully in their evacuation function. This issue was also raised following the evacuation of Asiana flight 214, which crashed at San Francisco in 2013, where slides inflated inside the aircraft cabin of the Boeing 777-200ER. Is adequate scrutiny being given to this repeated problem?

The issues go beyond previously identified concerns around the sufficiency of non-physical evacuation testing in increasingly dense aircraft cabins. Astoundingly, the GCAA report suggests that zero of the emergency slides functioned fully in their evacuation function. This issue was also raised following the evacuation of Asiana flight 214, which crashed at San Francisco in 2013, where slides inflated inside the aircraft cabin of the Boeing 777-200ER. Is adequate scrutiny being given to this repeated problem?

When modelling — physically or via simulation — aircraft evacuations, certification authorities require that 50% of the doors be operational. In practice, this means that half the doors on the aircraft are designated as inactive. In relatively recent initial physical testing for the Airbus A380 cabin, every door on the right hand side of the aircraft was rendered inoperable, which would simulate a fire or structural issue on that side of the aircraft. Questions exist over whether this adequately reflects the way and pattern in which doors are rendered inoperable or unavailable for evacuation in real-world situations.

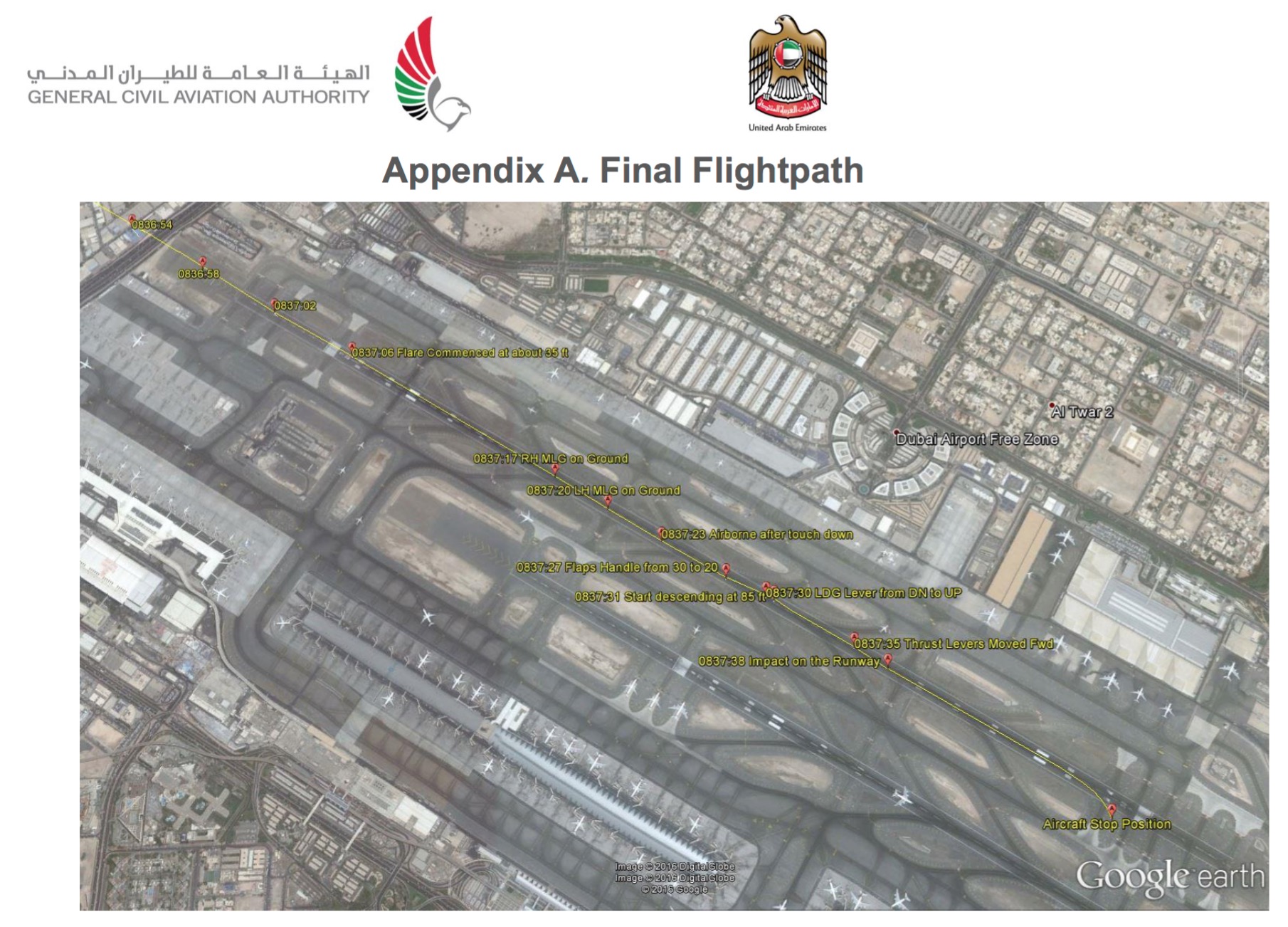

The aircraft aft fuselage lower section impacted first, followed by the engines, the lower section of the aircraft belly fairing, and then the forward fuselage and nose landing gear doors. The No.2 engine separated, moved laterally on the right wing leading edge, and remained near the right wingtip until the aircraft came to rest.

A runway camera recorded flame events, sparks, and smoke underneath the No.1 engine,at the separated No.2 engine, and at the damaged RH engine-pylon attachment. After the aircraft came to rest, fire continued on the detached No.2 engine, the damaged RH engine- pylon attachment area, the underside of No.1 engine and from under the aircraft fuselage. As the ARFFS crew were fighting the fire, an explosion occurred approximately nine minutes after the aircraft had come to rest. The explosion occurred in the center wing tank, causing a large section, approximately 15 meters in length, of the RH inboard wing upper skin to be liberated and blown several meters above the runway surface. The liberated skin landed near to the RH wingtip. Following the explosion, the dynamics of the fire altered with the fire migrating into the interior of the aircraft cabin, and at a later stage, into the cargo compartments.

The evacuation itself was riddled with issues around functionality of doors and slides, particularly in the winds present on the airfield.

Summarising the report:

Door L1 required two crewmembers to open, and the escape slide detached from the aircraft before passengers could use it. The door was blocked.

Door R1’s slide “slide was blown up by the wind and blocked the exit” during slide deployment. “At a later time during the evacuation, this slide settled on the ground and became available for some passengers and crew,” but this slide deflated during the evacuation and the door was again blocked.

Door L2 required two crewmembers to open, the slide did not touch the ground, and the slide was blown against the door by the wind. The door was blocked.

Door R2 was affected by smoke initially, and passengers were directed to another door (presumably rearwards). When the smoke cleared, this exit was used.

Door R3 was opened by a crewmember, but fire was spotted outside and two passengers were needed to close the door while the crewmember redirected passengers aft.

Door L4’s slide was blown up against the aircraft. The crewmember blocked the door.

Door R4 was opened, although the crewmember “did not hear the ‘evacuate’ instruction because of the noise level in the cabin”. After several passengers evacuated, they became stuck on the slide because it was “filled with firefighting water”

Door L5’s slide deployed, and “some passengers evacuated using this slide, but towards the end of the evacuation the slide was blown up against the door preventing further evacuation.”

Door R5’s slide deployed but was lifted off the ground by the wind. The crewmember redirected passengers to L5, until a firefighter saw the problem and “held the slide down”, enabling evacuation.

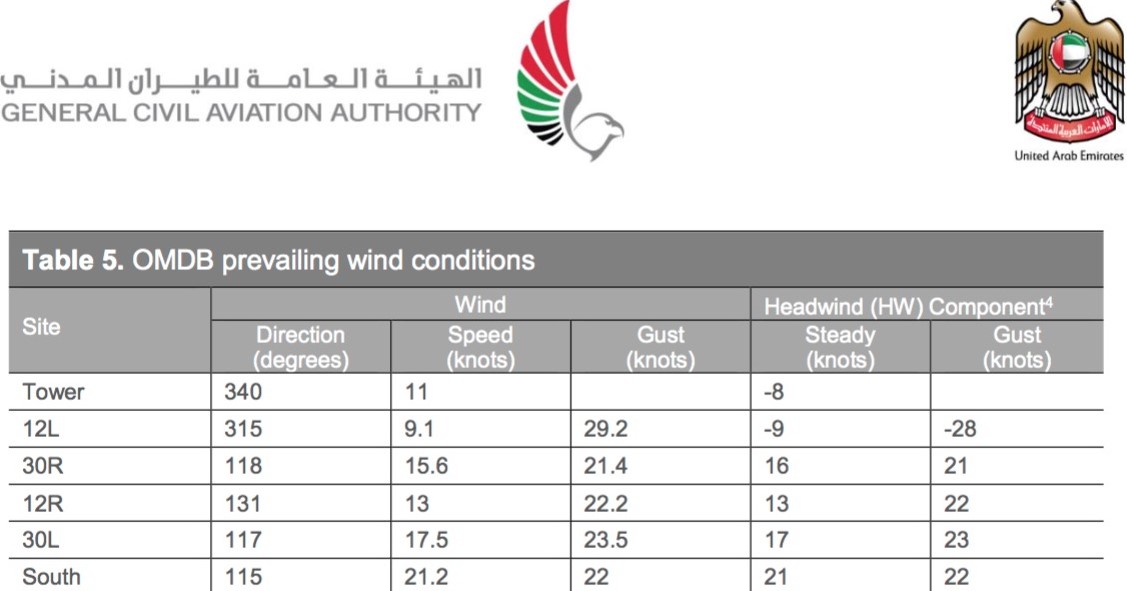

Wind strength was a significant factor in the unavailability of the slides, and the GCAA outlined wind readings at a number of positions on the airfield.

EK521 was to land on runway 12L, slid down the runway and completed its slide at nearly the start of 30R, which would thus be the relevant wind measurement for the evacuation process.

FAA regulations in 14 CFR 29.809 (g) (4) state that slides “must have the capability, in 25-knot winds directed from the most critical angle, to deploy and, with the assistance of only one person, to remain usable after full deployment to evacuate occupants safely to the ground”. This threshold would not appear to have been exceeded in this incident, raising clear questions about slide functionality.

Overall, it would appear that the evacuation took so long that “the commander and senior cabin crewmember were the last to exit the aircraft. They stated that they were still searching the cabin for any remaining passengers. When the center fuel tank exploded, causing intense smoke to fill the cabin, they attempted to evacuate from the cockpit emergency windows. However, as the cockpit was filled with smoke, they were unable to locate the evacuation ropes. Consequently, both evacuated by jumping from the L1 door onto the slide laying on the ground.”

The implication is that crew were still on board nine minutes following evacuation, which raises questions in and of itself — not about the laudable dedication by these crewmembers to ensuring that their passengers evacuated, but in the fact that they felt the search was necessary nine minutes after the aircraft came to a stop.

The US NTSB declined to comment on record given the ongoing nature of the GCAA investigation into EK521, and the FAA has not yet responded to RGN’s questions.

Top image: Konstantin Von Wedelstaedt, distributed under GFDL 1.2.