One of the knock-on effects of the proliferation of passenger-focused hardware innovations – from entertainment to connectivity to environmental improvements – has been a compounding variety of technologies for the human side of airline operations to deal with.

Whether that’s cabin crew needing to understand new systems, and of course to build operation and troubleshooting time into their busy workflows, or a wider variety of staff involved in managing an airline’s technological assets, the human factor is spurring changes as newer technologies advance a full version number.

Lufthansa Systems, for example, is redesigning the user interface of its newest BoardConnect Portable inflight entertainment system to make it more intuitive and easier to use, following feedback from crew that the user interface was perhaps not as simple during everyday flight operations as it might have seemed in the design stage.

Company head of passenger experience products & solutions Jan-Peter Gänse tells Runway Girl Network that, “We as ‘IT nerds’ sometimes come with a piece of technology that we believe to be easy to understand, but in reality, it is not. I have all the respect in the world for the job cabin crews around the world perform. The majority of crews I have met had been super nice, super professional and with a lot of enthusiasm towards their job. And just to make this clear, their job is not to operate a portable IFE solution. We need to ensure a better user-driven design that allows someone with a very busy schedule — there really is no time on short-haul flights to do anything extra — to not worry about the technology we have introduced. Actually, it should make their lives easier.”

“Painful troubleshooting”, Gänse says, identified a number of issues, as did a series of fly-alongs with crew. “Especially in the beginning before we automated the modem they had to turn it on during ground time – not only did they sometimes forget, but also finding the right button was an issue. Secondly, we did not think it through in terms of how can the crew best identify the status of the system. The new portable addresses all those issues and more.”

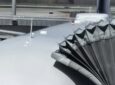

The new version turns a series of screens and swipe actions into a single screen with simple push-buttons and lights, and a display to indicate system status and for operation. Added to the new user interface is better hardware robustness and an x64 chip, increasing computing power and enabling third-party applications on board.

With the flap down, the new BoardConnect Portable has four buttons, each with a light and a section of the display screen for information. Image: Lufthansa Systems

Elsewhere in the cabin, German startup Jetlite – a participant in the début 2015 class of Airbus’ BizLab accelerator in Hamburg – is also designing more hardware automation into the second generation of its systems after monitoring the initial software-based rollout.

Developed based on academic research by managing partner Dr Achim Leder, Jetlite’s current implementation uses a chronobiological algorithm to determine what kind of light to use in the cabin in order to stimulate and suppress the body’s production of the sleep-producing hormone melatonin. Installed on select Lufthansa widebodies, Jetlite presently uses crew-controlled software to regulate the amount of blue light (which suppresses melatonin and therefore stimulates wakefulness) on board.

In essence, says Leder, “you don’t only switch the lighting on or off, but you dim it. You decrease or increase the cabin lighting in a slow process, and change the colours and the main spectrum of the light.”

During the process of designing Jetlite, Apple and other consumer electronics companies introduced Night Shift and similarly functioning systems, which shift the light from screens from primarily blue (daylight) to yellow (evening/night-time).

“Since you have [this kind of colour shifting] in the smartphones, people understand,” Leder says. “In the beginning, when Apple started, we said ‘oh, they’re stealing our idea’ — but it of course wasn’t our idea, decreasing melatonin. But since they’ve used it, we have a much better understanding [from] everyone about it.”

On long-haul flights, the spectrum shift is especially valuable: many regular travelers and savvy flyers know that exposure to daylight is beneficial to reset body clocks, but the amount and timing on longer flights is difficult to calculate. A compounding factor is the desire by crew and fellow passengers to draw the blinds and darken the cabin, even on day flights, to encourage sleep and reduce glare for inflight entertainment screens.

Enter Jetlite, where the algorithm creates cycles of blue and yellow light — roughly, Leder says, two full cycles for a 12-hour flight — based on what’s needed once passengers arrive at their destination. The issue is, at present, that however well the algorithm is designed, it relies on the crew activating it and using it properly.

“In the future, it will be a bit individualized depending on the route, but at present it’s individualized but dependent on the crew: you need the crew to understand the system,” Leder says, noting that while “it’s easy to understand, and we provide very good information to the airlines for the crews, and crew training,” levels of understanding and execution differ.

The learning point in this kind of systems design was certainly the case on a recent overnight Lufthansa A350 flight this journalist took from Boston to Munich, where any use of the system to manage passengers’ biorhythms was sorely lacking: for a start, crew had no idea what I was talking about when I mentioned the system or explained it. Indeed, the crew had the lights on full daylight blue mode during the late twilight boarding for an 8pm departure, but turned them largely off during the dinner service and afterwards, omitting any chance to try to reprogram body rhythms before sleep. Similarly, the lights were turned full on very quickly the next morning, missing the opportunity to use light-based waking.

By contrast, an algorithm would allow the crew to turn the intensity of the light up and down – for meal service, for example, or to attend to a passenger requiring assistance – but at a bare minimum would keep this light in the correct spectrum. It’s the difference between looking at a bright blue tablet or laptop screen right before bed and reading in the yellow light of a tungsten bulb, and there are real consequences to this decision.

Automation and user interface changes aren’t panaceas. But designing simpler, more intuitive, and set-and-forget user interfaces for the ever-increasing number of technology systems on aircraft is a prescription for better PaxEx.

Related Articles:

- STG adopts and improves Airbus LED lighting to enhance #PaxEx

- Kontron makes the leap into portable wifi and quickly gains traction

- The importance of service recovery: a case study

- Flight attendants need to feel empowered to fight harassment

- Airlines tighten contracts for portable wifi as they eye IFC upgrade

- Safer, powered, Iridium NEXT-connected BoardConnect Portable unveiled

- STG Aerospace is serious about LED lighting simplicity

- Boeing eyes nextgen lighting, projection technology for cabins

- Thomson turns to cabin lighting specialist to transform 737s, 757s

- Portable Wi-Fi boxes gain in popularity at airlines, but are they safe?

- Portable IFE specialist embraces suite of new cabin technologies

- Press Release: New gen BoardConnect Portable to be unveiled at APEX