Increasingly, inflight connectivity isn’t about the connection technology, but what passengers can do with it.

Increasingly, inflight connectivity isn’t about the connection technology, but what passengers can do with it.

This is going to be especially true as new and existing service providers roll out new and additional technologies worldwide: Gogo’s 2Ku, for example, Inmarsat’s much-delayed Global Xpress, or successive ViaSat satellites.

A complicating factor in helping passengers understand what to expect will be the move from connection technology as the determinant of service quality (regional Ka-band often great, broadbeam Ku-band and ATG-4 okay, legacy ATG meh, L-band bad) to a combination of provider and connection.

We’re already seeing this in Ku-band, with Panasonic’s product a reasonable experience, yet — as a Twitter search for “Southwest Wi-Fi” or a review of the airline’s FlyerTalk forum (post title: “Soooooo slowwwwww”) will show — Global Eagle’s Ku-band product less impressive.

It’s unclear whether this is a Southwest and Norwegian problem — the amount of capacity purchased (or not purchased) by the airlines — or an upstream issue with GEE’s capacity, though we’re told that Norwegian, at least, has contracted for a minimal amount of Ku capacity.

Regardless, neither Global Eagle nor its customers look good when the overwhelming narrative is negative.

Passengers by and large think of the connectivity service they receive as the airline’s Wi-Fi, whether or not it is branded with the airline’s identity, and irrespective of the underlying technology. Compounding the issue, airlines over-promise and underdeliver, as the passenger suing United for $5 million because she paid $7.99 for DirecTV live television that is inactive outside the continental United States discovered.

Compounding the issue, airlines over-promise and underdeliver, as the passenger suing United for $5 million because she paid $7.99 for DirecTV live television that is inactive outside the continental United States discovered.

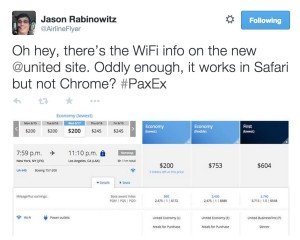

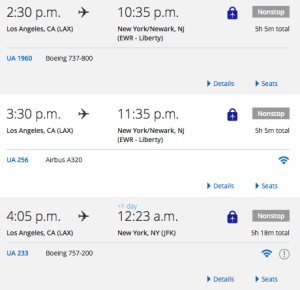

United is notable given that it wraps both Panasonic’s Ku-band and ViaSat’s Ka-band connectivity services in a UA frontend, making the specific type of Wi-Fi invisible to customers at the point of use (and, despite the promises of its new website, not entirely reliably at the point of flight selection, as the tweet below from Routehappy data researcher and RGN contributor Jason Rabinowitz shows).

That means that anyone who doesn’t know their Ka from Ku (a Gizmodo writer, say) will see an identical brand but receive a different service. It’s like walking into a mid-range restaurant, paying $20 for a main course and then randomly getting either a Big Mac and Coke or a Chateaubriand with a 1945 Chateau Mouton Rothschild Pauillac, depending on the table where you’ve been seated.

And that’s not even taking into account the Gogo experience on board United’s p.s. 757-200 aircraft. On the business-heavy p.s. transcons, which are laden with tech-savvy travelers, ATG-4 is like ordering too few sharing plates of tapas to go around — fine if it’s just you and a couple of friends, but shared between too many people it’s just not a satisfying experience.

Most United flyers don’t know which aircraft have which Wi-Fi provider, so completely unknowingly can have one of three different inflight connectivity experiences on United, even between the same cities.

It might also help if United’s website adequately represented the planned ViaSat installation completion dates of July and August 2015 for the 737-800 and 737-900 fleet.  The question will soon not be whether passengers have Wi-Fi. The question is whether or not they’ll be able to do what they expect with it. And the airline industry needs to take some urgent action to set those expectations, since passengers expect inflight Wi-Fi to work like home (or at least 3G) connectivity.

The question will soon not be whether passengers have Wi-Fi. The question is whether or not they’ll be able to do what they expect with it. And the airline industry needs to take some urgent action to set those expectations, since passengers expect inflight Wi-Fi to work like home (or at least 3G) connectivity.