In the United States, airlines must abide by laws including the Americans with Disabilities Act and Part 382 of Title 14 of the US code. In Europe, international legislation includes Regulation (EC) N° 1107/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 concerning the rights of disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility when traveling by air, plus numerous conforming national laws.

Yet from start to finish, airlines — and airports — are failing people who most need them to step up. And it’s virtually invisible to people who don’t require assistance.

Most passengers encounter fellow travelers requiring assistance only at the boarding gate, where they must often be helped through crowds of flyers pushing forward to be the first to board.

RGN has polled numerous people with disabilities, from Paralympic athletes to tech industry workers and journalists — all people who need to travel, but say they are being incredibly poorly served by the air travel industry.

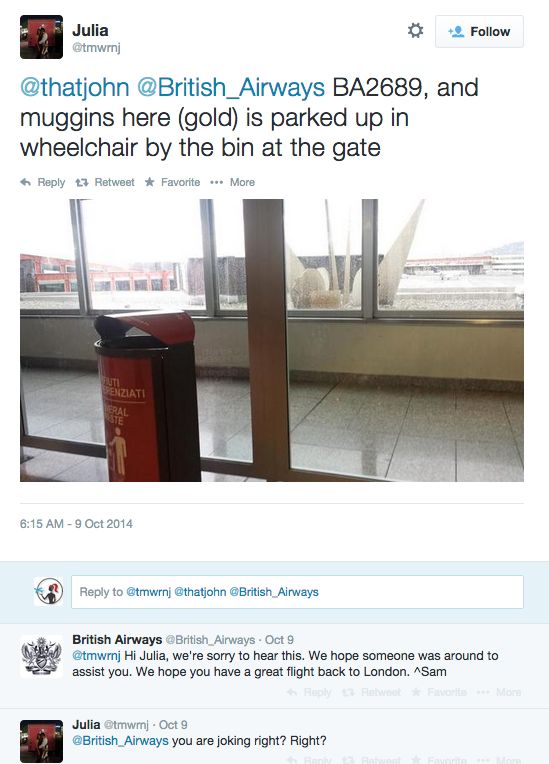

Here’s one passenger’s story to illustrate the gap between what some airlines promise, what they deliver and what many people would think they should be delivering, from British travel journalist Julia Buckley, who has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a joint disability.

Explaining her situation, Buckley tells RGN, “My joints are hyperflexible and can dislocate very easily, even when doing something other people take for granted like cleaning the hob. I can’t walk long distances because it’s painful and I tire easily. I’m not supposed to lift or carry heavy things (like suitcases) because I can injure myself easily. It affects my nervous system/heartrate so standing for long periods or waiting in line can make me faint. It’s also a chronic pain condition so I am pretty much permanently in some level of pain.

“I’m lucky enough to have it relatively mildly compared to other people and to be very mobile,” Buckley insists. “I use a stick most of the time (not if I’m just going to the shop) but I can walk. And if I don’t have my stick it doesn’t look like there’s anything wrong with me. I think that is why I get a lot of resistance when I request assistance. But I always ask for assistance, even on a good day, because I know that I only have a certain amount of energy for the day, and I can injure myself very easily. If I have a bad flight, it can knock me out for a week or so. I think that’s quite an important point, actually – you don’t have to be in a wheelchair to require assistance (the clue is in the name).”

Buckley’s circumstances require physical assistance at three main points in the journey.

First, lifting her bag onto the belt at check-in, because her shoulder can dislocate if she lifts it herself. She notes that some airlines are happy to assist with this, whereas others — she names British Airways in particular — resolutely refuse, saying it’s against policy. “Then I have to move down the line to another check-in agent until I find someone prepared to break the rules,” Buckley says.

Second, a wheelchair to the gate, from check-in through security and to boarding. But in reality, Buckley explains, “I quite often have to navigate security myself because the assistance takes so long to arrive (in which case I have to ask security staff to let me sit until my place in the line comes up or skip the line) and need someone to lift my stuff onto the belt.”

While Buckley has frequent flyer status on oneworld and Star Alliance, she says she is often refused lounge access — not by the airline, but by the assistance staffers who don’t want to assist her to the lounge and then to the gate, so she ends up wheeled to the gate two hours before the flight.

She says British Airways in particular has insisted on not wheeling her the short way from Fast Track security in Heathrow Terminal 5 to its Galleries lounges, but rather forcing her the long way around, down and up to the crowded main shopping precinct, where she is more likely to be bumped into and potentially injured by careless passers-by.

Lounge access is important to Buckley, and not for the champagne-swilling, caviar-munching reasons that most frequent flyers expect. “This might very much seem a first class problem,” Buckley is the first to say, “but if I’m wheeled straight to the gate and seated in an airport wheelchair for two hours my pain levels have risen considerably, and then I have to face the flight. Many people with disabilities will need extra time before boarding — to take meds, check they have all the equipment they need for the flight, get some time to lie down or stretch before boarding, and so on. Everyone’s circumstances are different, but it seems like nobody is being served well right now.”

An example: “Last December flying Las Vegas-London Gatwick on Virgin Atlantic, I had used miles to upgrade to Upper Class so was looking forward to the lounge. But the assistance never arrived so I waited by the check-in desk for nearly an hour. Eventually one of the check-in staff stole a wheelchair and took me airside himself, but it was so late that I had 5 mins in the lounge – just enough to slug my preflight painkillers and go to the loo – before I had to board.

Third, Buckley requires assistance putting her carry-on bags in the overhead bin, again because she can dislocate her shoulder with even the lightest-packed bag. “Flight attendants often refuse to do this, or get upset, assuming I’m asking because I’ve overpacked my bag rather than because I can’t lift anything. Normally once I say I’ve had assistance someone will help, because when you book assistance they promise to help with this. But there seems to be no link between airline reservations, check-in desks, contractors who take me to the gate, and the cabin crew. I have to explain my needs at every step of the way.”

Fourth, Buckley needs a wheelchair from the aircraft to the exit. “This is crucial because whatever the length of flight, whatever the class of travel, I’m in more pain when I get off than when I boarded. Usually I have to wait for the rest of the plane to disembark before I’m allowed to get off, and often (pretty much always at Heathrow) the wheelchair isn’t there. I missed my British Airways connection this July at Heathrow Terminal 5 because assistance didn’t arrive in time.”

Buckley also needs back-office assistance when selecting seating. “Don’t we all love extra legroom seats?” she laughs. “But I need to be absolutely sure which seat I’m getting because I have to keep my spine straight, and a trapped nerve in my neck and right arm means I can’t be sharing an armrest or crushed against a window. So I need an aisle seat on the left-hand side of the aircraft, and preferably a bulkhead. Most airlines claim to have special seating arrangements for disabled passengers, but it nearly always falls through and it is enough to give you a breakdown trying to book it.”

Buckley says, “I had a very poor experience with Singapore Airlines this week. I’d heard they’re great for wheelchairs and have accessible lavatories, which is really important for long-haul flights, but when asking for a bulkhead seat I was told they’re all for infants, and if at check-in there’s one available they try to prioritized disabled people, but there are no guarantees. That’s a poor policy compared with most other airlines and would make me — and other people who need assistance — steer clear, since I need to be sure of my seat when I book flights so that I’m not injured, especially long haul.”

Singapore Airlines confirmed that it prioritizes infants over people with disabilities, with this from spokesman James Bradbury-Boyd: “We make every effort to ensure that passengers with limited mobility are provided aisle seats to accommodate their needs — particularly as bulkhead seat armrests are not retractable, making seat-to-wheelchair transfers difficult for many travelers. We make a similar commitment to passengers traveling with infants, giving them priority for bulkhead seat assignments when available, as these are the only points aboard the aircraft where bassinets can be installed. At the point of departure, should bulkhead seating be available, we are happy to assign it to passengers with disabilities upon request.”

FAILING IN FOUR KEY STAGES OF THE PASSENGER JOURNEY

The repeated failings by airlines are clear from Buckley’s experience — and they sync with the stories of other people requiring assistance we spoke with, including Paralympic athletes and less mobile elders.

Buckley identifies four key points in the journey where airlines’ required provisions for people requiring mobility assistance fail:

1) Some airlines don’t have clear policies for what they offer to customers needing special assistance, and they are dreadful at sticking to those policies even when they do. Virgin Atlantic is an exception, says Buckley. “It has a designated special assistance team, so they know everything you could possibly want to know about how your flight is going to go, and what they can offer you. They’re the only airline I’ve used who does, though – everyone else just uses generic customer service staff.”

2) “At the airport, the airline and whoever provides wheelchair assistance are almost always on a contractor basis, and don’t seem to work together or have any accountability at all. I’ve experienced numerous situations where the airline doesn’t make the arrangements, the assistance doesn’t turn up, it turns up late, airline staff fail to chase it so I’m left standing at check-in, and complaints never seem to make a bit of difference,” Buckley explains.

3) Airlines often fail to do the back-office work that they promise. Buckley has been promised seats that meet her needs and then not provided with them, and staff at the airport or on the plane are frequently not notified that she requires assistance onboard.

4) Staff training is also woefully inadequate. “It is unreal how untrained people are. At best, I’ll describe my seating needs to someone on the phone and ask for advice as to which seat will be best for me – and they won’t know the seating plan well enough. At worst, airline staff are outright aggressive with me. I was once told by a British Airways person who refused to book me a bulkhead that I was “lucky” to be being assigned a seat for free (and this when I was a Silver frequent flyer at the time, which includes free seat assignment) and should take what I was given. Staff have refused to help lift my case onto the luggage belt at check-in.”

“But the worst,” Buckley says, “is that they’re not trained in special needs, and they make assumptions. When flying from Heathrow to LAX on Virgin Atlantic this year, I arrived at the Upper Class Wing and the check-in staffer looked me up and down and said, ‘It says here you require a wheelchair to the lounge but you’re ok to walk, right? It’s not far’. I felt so mortified that I agreed to walk, injured myself at security, and was wiped out by the limp to the lounge.”

RGN timed this walk the last time we flew Virgin Atlantic this year, and a fully mobile person can do the walk in five minutes, dodging people meandering through the duty free shop (there is no opportunity to avoid the crowd). For people with disabilities, the walk will take much longer and comes at a significant risk of injury if unable to move quickly enough to evade milling shoppers, running children and inattentive passengers with shopping carts and rolling luggage.

RGN timed this walk the last time we flew Virgin Atlantic this year, and a fully mobile person can do the walk in five minutes, dodging people meandering through the duty free shop (there is no opportunity to avoid the crowd). For people with disabilities, the walk will take much longer and comes at a significant risk of injury if unable to move quickly enough to evade milling shoppers, running children and inattentive passengers with shopping carts and rolling luggage.

Buckley gives another example: “Cabin crew on Air Europa once said to me when I’d got up to look for the wheelchair that had never arrived, then asked to sit back down, ‘If you just managed to walk now, why do you need a wheelchair?’ A British Airways cabin crew person told me I’d have to run down a spiral staircase to catch a transfer bus in time in May, because the wheelchair hadn’t arrived. Luckily I can walk, but many people who require assistance can’t.”

5) Most damningly, some airlines fail to improve even where people with disabilities tell them exactly what’s going on and where they have failed. “I have tens of thousands of avios as ‘compensation’ for assistance going wrong on British Airways,” Buckley says. “I have a written apology from Virgin. I don’t care about either of those things. I want to make sure things don’t go wrong next time, and that they don’t go wrong for other people. I complain a lot about assistance issues, because I think it’s important to do so for those who fly less frequently and who need it more. But nothing ever changes. Often — like when dealing with Air Europa and Heathrow Airport — I don’t even get a response to my complaint.”

“If I have an issue at Heathrow,” Buckley explains, “I have to deal with British Airways, because Heathrow Airport and Omniserv contractors answer to them and not to me. Yet when I tell BA there are issues, their response is always ‘it’s not our problem, it’s Omniserv’.”

PR PLATITUDES ARE ON A DIFFERENT PLANET TO PASSENGERS’ REAL EXPERIENCES

It might seem almost inconceivable for able-bodied people that airlines and airports are failing our less able-bodied fellow travelers so badly.

And it seems that they know they’re doing so poorly. This RGN writer contacted airlines and airports with several specific problems Buckley was experiencing. Her problems disappeared quickly. Airport social media teams resolved problems. Airline PR representatives fixed the issue within hours. Management contacted her offline.

But not every person requiring assistance knows an aviation journalist whose inquiries make airlines and airports jump to fixing problems. And they shouldn’t have to.

We contacted Heathrow Airport and British Airways for comment on what Buckley encounters when she flies. Both responded with lengthy brush-offs containing platitudes and policy assertions — to which Buckley was able to immediately respond with specific examples of where the airline and the airport’s real-world actions were contrary to the policy their PR departments told us.

As an industry, we need to do better.