It was with some excitement that Runway Girl Network, sifting through the seatback pocket of a recent British Airways A320 flight from Lyon to London Heathrow, discovered a rather battered printout noting that the airline provided inflight connectivity on this aircraft, registration G-EUUG. Unfortunately, the performance of the European Aviation Network hybrid S-band/air-to-ground system was rather “euug” itself, with British Airways — and its supplier — needing to up their connectivity game.

It was with some excitement that Runway Girl Network, sifting through the seatback pocket of a recent British Airways A320 flight from Lyon to London Heathrow, discovered a rather battered printout noting that the airline provided inflight connectivity on this aircraft, registration G-EUUG. Unfortunately, the performance of the European Aviation Network hybrid S-band/air-to-ground system was rather “euug” itself, with British Airways — and its supplier — needing to up their connectivity game.

Skipping straight to the service, RGN purchased the £6.99 (approximately US$9, and a dollar more expensive if purchasing in USD) “Browse & Stream” package, which advertises “high-speed web browsing”, “video streaming” and “one device – continuous use”.

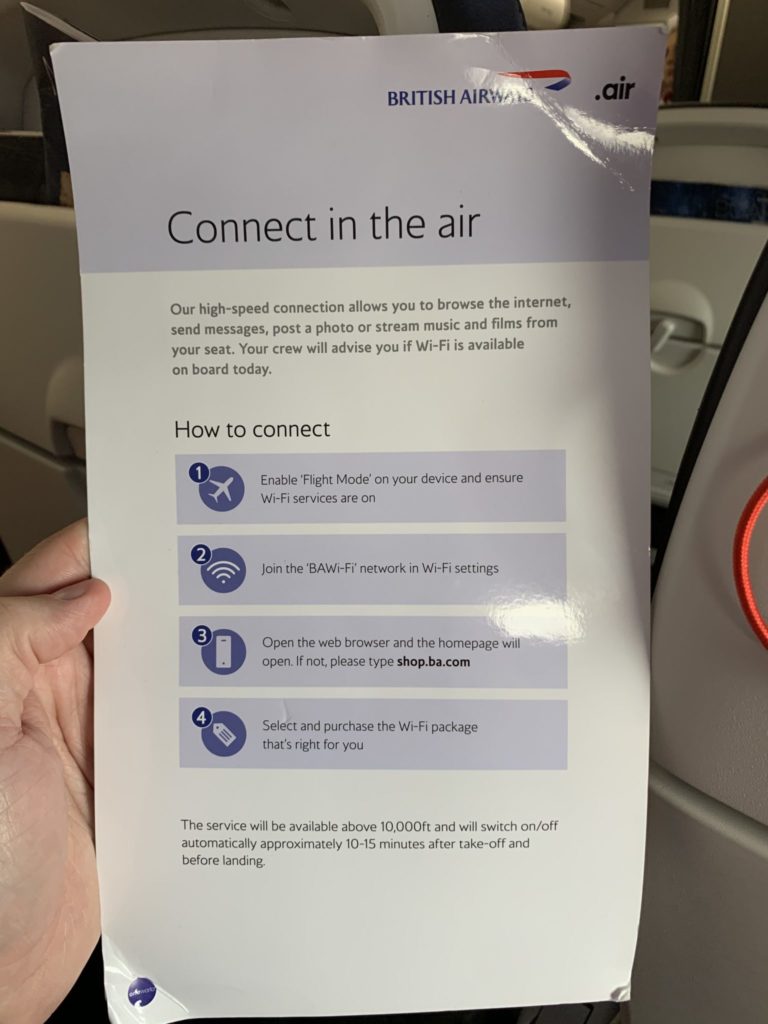

The rather unloved-looking cards are the only way you might know there’s connectivity on board. Image: John Walton

This was not your RGN journalist’s first outing with inflight connectivity, and clicking through to the terms and conditions revealed the disappointingly uncompetitive data restrictions: after 50MB are used within 30 minutes, the rest of the hour is in the slow lane.

The first 50MB are advertised at “full speed”, which is consistently blocked to under 1Mbps, with multiple tests showing speeds in the 0.9 Mbps range up and down, until the risibly low cap of 50MB was reached, at which point it was slowed to 0.6 Mbps. Latency was consistently low, 50-60 ms, suggesting that the system was using the air-to-ground-based element of the EAN.

Inmarsat rivals Viasat and Eutelsat believe the EAN overwhelmingly relies on the terrestrial portion of the network, and they’ve fought the EAN in court. In February, a Belgian court punted questions to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) about the timing of Inmarsat’s deployment of the S-band satellite. In doing so, the Belgian judge asked whether national regulatory authorities must deny authorization of the EAN based on the obligations of the original mobile satellite service (MSS) tender decision.

Now the French have weighed in. The “Conseil d’Etat” (Council of State) has stayed the proceedings in Eutelsat’s appeal against French telecommunications agency Arcep’s 22 February 2018 decision authorizing Inmarsat to operate terrestrial relay antennas which it uses to market its inflight Internet offer in France.

As in Belgium, the French Conseil d’Etat has referred several preliminary questions to the ECJ, says Eutelsat in a statement. “This decision by the Conseil d’Etat confirms the uncertainties raised by Eutelsat as to whether the Arcep decision complies with European regulations regarding the conditions for operating a mobile satellite system, as Eutelsat considers that this system should be predominantly based on a satellite system, and not on terrestrial relay antennas.”

The ECJ process can take many months to resolve.

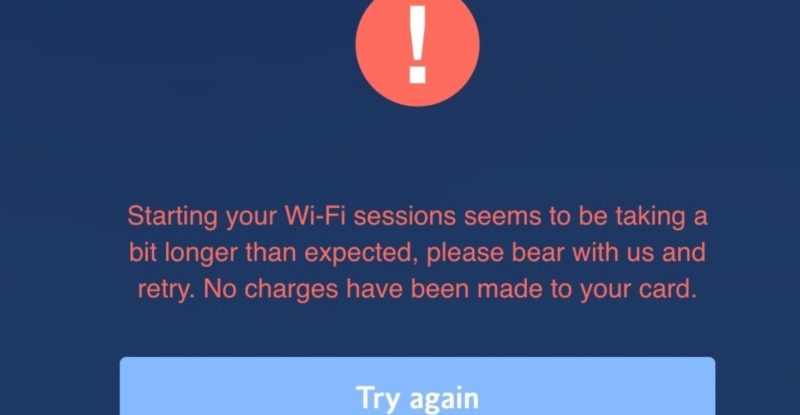

This level of restriction is not acceptable for the pricing level or market context in which BA and the EAN are playing. Screenshot: British Airways

Meanwhile, with respect to the EAN service offered by British Airways and tested by your writer, there are real trading standards questions to be answered about whether sub-1 Mbps counts as the “high-speed web browsing” that BA is selling. The UK government [pdf, 6MB] defines an “acceptable broadband speed” as 10 Mbps down and 1Mbps up.

Given the supposed cost advantages of the EAN’s hybrid air-to-ground system over pure satellite connectivity, it is surprising that either the system did not perform better than this or that its airline customer decided to provision so low a level of performance.

Beyond the tests, real-world streaming performance on RGN’s iPhone XS Max was surprisingly poor. Despite multiple advertisements for Netflix on the portal, this service performed the weakest of the three video streaming services RGN tried (Netflix, YouTube and the BBC’s iPlayer).

BA advertises Netflix in multiple places (alongside a nearly 24-hour flight time). Screenshot: British Airways

Netflix barely worked at all, failing to load thumbnail imagery, buffering for minutes and then playing only intermittently. RGN would classify this as “did not work”.

YouTube, where resolutions (and thus rough bitrates) can be set, was stop-and-go buffering at 720p or above, intermittently stop-and-go at 480p, but worked at 360p, although this is very much not a good service even on a phone.

The BBC’s iPlayer — which, interestingly, worked on the aircraft despite the iPlayer being geofenced to the United Kingdom — worked, but at a low resolution on the phone.

The rest of the Internet was fine, though: uploading images to messaging apps and Twitter was remarkably swift, and even WhatsApp video and FaceTime both worked, to an extent. Calling RGN contributor Jason Rabinowitz in New York to test, it was interesting to note that the performance of two-way video was better on the aircraft using WhatsApp, but better via FaceTime on the ground.

Another takeaway from the flight was that British Airways also needs to work on the way it advertises and manages its connectivity, beyond calling 1 Mbps “high speed” and imposing a 50 MB ceiling for the data throttle.

To start with, there was no announcement from the crew about the connectivity, which is a lost opportunity. Nor was there any notification on BA’s app. But it’s also true that Inmarsat says the carrier is in “soft launch”.

The cabin crew also seemed poorly briefed: when the connectivity part of the system did not go live at 10,000 feet this journalist asked whether it was working properly. “I’m not sure if it’s on this plane,” said the crewmember.

After being showed the leaflet and the phone displaying the portal, the answer turned into “I’m not sure if we’re cleared with regulations to turn it on,” suggesting that there remain some jurisdictional issues with the system.

It did, eventually, go live — but it is not gate-to-gate, restricted to operations above 10,000 feet, which is a disadvantage on shorter flights like BA’s European routes (and comes at a time when European carriers are touting gate-to-gate). Does this height restriction imply that the EAN is presently only using its air-to-ground functionality and not the satellite connectivity?

The user interface of the web portal was surprisingly poor, with numerous elements overlapping. The captcha code required several goes, and the system for some reason hung on during the purchase process when using a laptop, but worked fine on an iPhone. The flight details on the portal also suggested a flight time of over 23 hours, which made this journalist smile in the context of the ongoing farrago regarding longhaul narrowbodies.

It’s also not possible to switch between devices, even when creating an account. This is sub-par and disappointing — even more so since it’s not made particularly clear, and given the rest of the market generally permits this it would be a reasonable expectation to be able to do so.

RGN asked British Airways to confirm whether the system was working as intended on this flight, although given the small-print restrictions we have no reason to imagine it was not. An airline spokesperson said: “The engineers have confirmed that WiFi was working on your flight. It sounds like there was a brief window when switching between cell towers that the service levels dipped so could not support streaming for a short time.”

The switching was not a noticeable problem, yet, overall, the design and performance of the system was so poor that, on consideration, this journalist would have asked for a refund. It is to be hoped that it improves dramatically during and after the rollout.

Related Articles:

- British Airways quietly launches European Aviation Network service

- EAN spat still has legs as Belgian court punts questions to ECJ

- Lufthansa Systems touts smart caching in advance of EAN launch

- Panasonic deploys Gen 3 network to relieve IFC service choke points

- Global Eagle expects IFC on Air France A320s to set European standard

- Gloves are off as Viasat CEO talks IFC opportunities

- European Aviation Network quietly ramps up despite objection

- Viasat will continue to challenge EAN despite recent Inmarsat win

- Fight for European tails amongst connectivity providers is intense

- Commercial launch of European Aviation Network moves to the right

- Inmarsat says EAN remains on track despite Belgium court decision