Since last December, Icelandair has been operating TAMDAR airborne meteorological sensors via a four-channel Iridium-based integrated communications unit. Though this aspect of Panasonic Avionics’ business flies a little more under the proverbial radar, TAMDAR (Tropospheric Airborne Meteorological Data Reporting) is at the forefront of weather forecasting and forecast production in four dimensions — time being the key addition, and the frequency and coverage of the aviation-based system the key enabler.

Icelandair’s operational requirements for the system specifically included a system separate from its existing Global Eagle Entertainment-provided Ku-band satellite-based inflight Internet system. The airline is very clear that this requirement was driven by safety — which is a notable data point in the discussion around whether operational and safety connectivity services should be separated from passenger services.

But transmitting over a narrowband system needs to be done thoughtfully due to cost, and Icelandair seems to be doing just that. Data compression is a vital part of making the economics of the system work, and Icelandair has developed in-house algorithms to use as little narrowband capacity as possible, RGN learned during a deep dive discussion with Icelandair execs.

Also reducing data usage is the pattern of transmission. Meteorologically speaking, data from the troposphere above 20,000 feet are less useful than the data from that level. While the aircraft may transmit as frequently as once every ten seconds during climb and descent (whether into Keflavik or an outstation), that interval stretches as long as seven minutes during the cruise period.

That 20,000 feet level sweet spot is one of the reasons why regional turboprop operators (like Flybe, Era, PenAir) and jet carriers with high frequencies and short stage lengths (like new TAMDAR customer AirAsia and US regional operators) are particularly well suited to the task of gathering meteorological information. Icelandair is currently trying to get its own domestic operator, Air Iceland, involved in the program.

RGN extrapolates the logic in this to suggest that, if Icelandair did not fly so frequently from a meteorologically important, low-data area, it would not be an early choice from the perspective of the wider TAMDAR network given its relatively long average stage lengths. Air Canada may well be in a similar situation, although its extensive Air Canada Express regional network would likely paint it in a more attractive light.

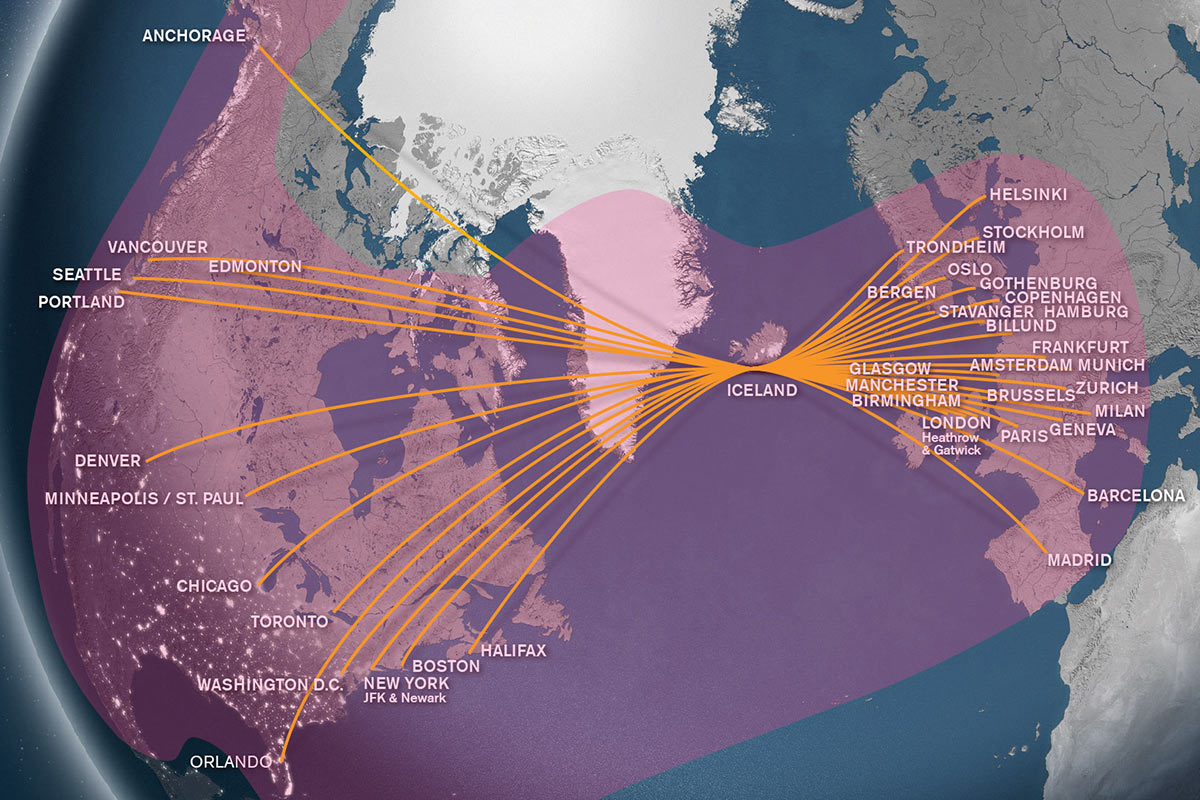

The geographical location of Icelandair’s Keflavik hub (the in-house joke is that it is a slightly oversized aircraft carrier in the middle of the North Atlantic) is both a benefit and a drawback.

On the one hand, the airline operates in a vital geographical niche, with cold fronts flowing down from Greenland and the Atlantic Current pushing systems up from the US eastern seaboard. Its extensive route network (including over northern Canada, where TAMDAR data were not being collected) flying in many directions makes Icelandair a useful partner. Data for this region, sitting as it does a matter of days in advance of Europe, and significantly affecting the track of north Atlantic flights — together with the data from the rare flights over northern Canada that Icelandair operates — are incredibly valuable.

Customers include Icelandair for its own operations, other airlines and meteorological organisations. More widely, products are used by numerous industries ranging from aviation to oil/gas derivatives markets to electrical utilities on both sides of the Atlantic (who boost production when it can be predicted that extra heating will be required in winter and extra cooling in summer).

On the other hand, transmitting the data is complex, particularly at the latitudes at which Icelandair flies. KEF itself sits at 64° North, while flights to Seattle often cross the 73rd parallel and even fly as far north as 75°N. The antenna angle and coverage issues at these latitudes are well-known.

The installation process (particularly initially) required a heavy maintenance check in order to program on-the-ground time. The first operational aircraft was Icelandair’s Hekla Aurora special liveried aircraft, which took to the skies in December 2014. The airline’s in-house MRO operation in Keflavik managed to fit seven aircraft before the pressures of the increasingly long summer schedule (Icelandair’s high season) required the fleet to be in the air rather than on the ground. Panasonic and Avionica were involved on the ground with the first two installations. With the summer drawing to a close, the program should resume shortly, will be undertaken outside the heavy maintenance checks, and is expected to be complete by the spring of 2016.

For Icelandair, the benefits of TAMDAR are numerous. On a tactical level, the system increases the tactical awareness of pilots to make more timely operational decisions (like flying with/around the jet streams on flights to northeastern North America), in conjunction with other connected aircraft systems like electronic flight bags.

More widely, the system enables Icelandair to take strategic operational decisions, like dynamically managing its arrivals flow into Keflavik in order to make its hub operations more efficient. As an example: an aircraft is delayed with a longer than expected outstation departure taxi time, which Icelandair says is the variable that impacts it most, and by the same token the variable that it can control least. If that late aircraft has a relatively high number of passengers with tight connections, it can be instructed to speed up and slotted in for arrival before other aircraft in order to reduce knock-on delays and minimise the number of passengers inconvenienced (not to mention the resulting overnight costs for the airline at Keflavik).

And even without the connecting passenger impetus, the system enables pilots to calculate real-time changes to their cost index (largely around whether to burn more fuel to go faster) in order to improve both on-time performance and turnaround efficiency at Keflavik.

The system can also be used to fulfil the requirements for the ICAO flight tracking mandate (which Icelandair quoted as a ten-minute interval, although the exact numbers may still be under review).

Finally, the data collected improve meteorological forecasting from Icelandic and other weather organisations — so, yes, the result of the aurora-themed aircraft’s first-in-fleet weather forecasting unit means that Iceland’s actual aurora borealis forecasting improves. Poetic symmetry indeed from the land of the Saga.