With the otherwise praiseworthy Delta CEO Richard Anderson appearing to link the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 to the rise of Emirates, Qatar Airways and Etihad (which was founded two years later in 2003), the US airline industry’s rhetoric has hopefully reached a nadir.

With the otherwise praiseworthy Delta CEO Richard Anderson appearing to link the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 to the rise of Emirates, Qatar Airways and Etihad (which was founded two years later in 2003), the US airline industry’s rhetoric has hopefully reached a nadir.

When asked about government subsidies and tax arrangements like Chapter 11 bankruptcy allowing airline restructuring on Richard Quest’s eponymous CNN show, Anderson said, “It’s a great irony to have the United Arab Emirates from the Arabian Peninsula talk about that, given the fact that our industry was really shocked by the terrorism of 9/11, which came from terrorists from the Arabian Peninsula, that caused us to go through a massive restructuring.”

Let’s be clear: after a week where three Muslims were shot in the head, execution-style, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to little apparent concern of some media outlets, we should have no compunction in condemning these types of analogies in the strongest of terms.

Nor should Anderson’s multiple “Barack Hussein Obama” style references to the “United Arab Emirates” on the “Arabian peninsula” be overlooked.

But it’s not just about what appears to be disappointingly casual anti-Arab sentiments.

The United States has pursued bilateral and multilateral Open Skies agreements for over 35 years, giving significant benefits to passengers and to economies on all sides of the agreements.

Over a hundred have been signed since 1992, to the general benefit of the US carriers, US passengers and the US economy. Yet after taking their share of the rewards, the US airlines have been moving to constrain competition on some routes so others may not also benefit, even while they are pleased to profit from new agreements (like the recent US-Mexico deal) where they hold the upper hand.

Across the Atlantic, the three principal joint venture agreements (Delta-Air France-KLM-Alitalia, United-Lufthansa-Swiss-Austrian-Brussels-Air Canada, American-Finnair-British Airways-Iberia) as well as bilateral agreements like Delta-Virgin Atlantic, quite specifically allow fare collusion, create significant barriers to entry for new carriers and give passengers less choice.

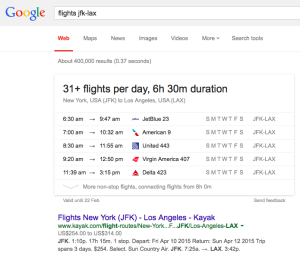

There is no good reason why price ranges quoted by Kayak should suggest JFK-LHR roundtrips (which Google Flights averages as 7 hours) should range from $672-$976 while JFK-LAX roundtrips (which Google Flights averages as 6 hours 30) range from $254 to $314.

Other joint ventures operate, notably across the Pacific and to and from Australasia. Yet all three US carriers have the temerity to object when new airlines — carriers that are organising and domiciling themselves for operational efficiency just as US carriers do — want to service US ports.

They use their influence to argue against Norwegian beginning its Ireland-headquartered low-cost service, at least partly on the basis that workers are subcontracted, even while contracting out a significant proportion of mainline and regional flying to US regional airlines and outsourcing operations at dozens of airports, even including hubs like New York and Denver.

They perpetuate thinly veiled objections about the growth of the Gulf network carriers (perhaps oddly for American, which has bilateral and alliance agreements with Etihad and Qatar Airways) in the post-9/11 corollary to Godwin’s Law.

With Emirates announcing its fourth daily JFK-Dubai service (this one via Milan), and the progressive upgrading of Boeing 777-operated services to A380s at other US airports, get ready for more accusations of unfair advantages and capacity dumping — surely not the sort of thing that the three US airlines would ever consider doing to new entrants, of course, and a little more than tinged with hypocrisy given that US airlines receive nearly a billion dollars of tax breaks for jet fuel alone, according to a study by Unite Here.

With Emirates announcing its fourth daily JFK-Dubai service (this one via Milan), and the progressive upgrading of Boeing 777-operated services to A380s at other US airports, get ready for more accusations of unfair advantages and capacity dumping — surely not the sort of thing that the three US airlines would ever consider doing to new entrants, of course, and a little more than tinged with hypocrisy given that US airlines receive nearly a billion dollars of tax breaks for jet fuel alone, according to a study by Unite Here.

Delta CEO Anderson’s ill-advised (at best) comments will do him no favors in his ongoing battle against the US Export-Import Bank, a loan guarantor that ensures that overseas customers of US businesses (notably including Boeing) without access to commercial loans can access credit to purchase US goods. Anderson has argued that the Ex-Im Bank gives an unfair advantage to foreign carriers like Emirates, Turkish Airlines and Korean Air, which he considers should have reasonable access to credit markets, allowing them to finance Boeing widebodies that then compete with Delta’s services. (Clearly, there is no love lost between the SkyTeam partners in Atlanta and Seoul.)

If the once-again profitable US major airlines think they are being out-competed by the Gulf carriers then the answer is innovation, not protectionism. It’s a rare passenger that would choose one of the big three US carriers’ flights on the basis of passenger experience over Emirates, Etihad or Qatar.

Perhaps if the carriers worked on becoming airlines of choice, with industry-leading hard product, soft product and services, with loyalty programs that made headlines for expansion rather than cuts, with newsworthy onboard and airport improvements rather than attempts to outdo each other in the race to the #PaxEx bottom, instead of complaining about notional advantages while ignoring their own, they might glean more sympathy.