For years, passengers in the United States have come to expect that the lion’s share of their domestic flights will offer inflight connectivity, even if they don’t always (or even often) experience an at-home experience in the sky just yet. To quote Emirates executive Patrick Brannelly, Wi-Fi is like air. People simply expect to have the choice of connecting to their families, friends, work and social networks.

Indeed, many people believe connectivity on the ground is a human right; how long before passengers view it in the same light in-flight?

But while the #PaxEx benefits of inflight connectivity are clear, somebody has to pony up and pay for the cost of hardware and service. In some instances, airlines have turned to the inflight connectivity providers for help, under agreements that would see the providers subsidize the hardware with the promise of revenue from paid sessions and advertising. That hasn’t quite worked out as hoped, with financially struggling Gogo – the dominant provider of connectivity in the US – now seeking to renegotiate some of its subsidy-influenced deals.

However the cost of connectivity service is covered – be it by sponsorships, charging passengers outright, or wrapping it into the cost of a ticket – it makes sense for industry to strengthen the business case for connectivity outside of the #PaxEx realm. The operational benefits of having a connected fleet are manifold and have been discussed for years. Connectivity can enable the delivery of aircraft health monitoring and maintenance data in-flight to improve turnaround times on the ground; it can support real-time credit card transactions; and it can ensure that pilots have live satellite pictures of weather on their electronic flight bags in the cockpit.

Last year, the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) released part one of three planned “Sky High Economics” reports detailing the wide-ranging effects of connectivity on the airline industry. Sponsored by Inmarsat, chapter one naturally quantified the commercial opportunities of passenger connectivity, while chapter two – which is authored by Dr. Alexander Grous of LSE’s department of media and communications and was unveiled to great fanfare at the recent APEX TECH conference in Los Angeles – went in an entirely different direction.

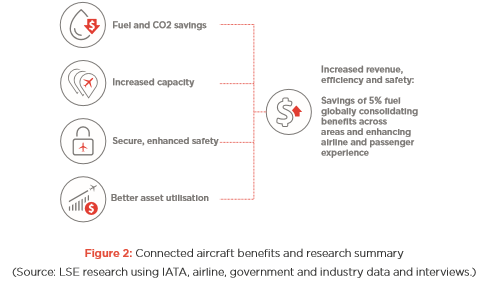

Focusing on the economic benefits of connectivity from a broader, operational perspective, Sky High Economics Chapter Two predicted that connected aircraft will have the potential to save airlines $11 billion to $15 billion annually in operational efficiencies and a whopping 21.3 million tonnes of CO2 emissions by 2035 – which is roughly the equivalent of taking 3.5 million cars off the road forever.

RGN sat down with Inmarsat’s senior vice president, market & business development, Frederik van Essen, and even he admitted that he was surprised by some of the report’s findings. “The headline figure of $11 billion-$15 billion itself surprised me,” said van Essen. “But I think if you look at some of the environmental benefits that are quoted, like regarding the amount of CO2 emissions that can be saved through flight optimization … that is a serious amount [and] it is stuff that [airlines] can do pretty easily that will more than pay for itself.”

“Things like biofuels, for example, or new generation engines, or even electric planes, these things are much harder to do. Which isn’t to say that you shouldn’t be doing them, but it takes much longer to get there. And so, things like dynamic route optimization can help the industry to legitimize itself that it is actually contributing to the environment or trying to contain its emissions while on the way to get there. And I think that is something that, to me, really stood out.”

And though connectivity does come at a price and broadband antenna radomes atop fuselages can add a slight drag, van Essen suggested that, sometimes – as recent real-world examples like the Kilauea volcano eruption in Hawaii have demonstrated – the economic impact of not connecting can prove to be even more costly.

While it doesn’t offer passenger connectivity, “Hawaiian Airlines now has an electronic flight bag that is updated live through the connectivity [Inmarsat’s SwiftBroadband-Safety service for the cockpit] so if there is new information on turbulence, or bad weather, or the volcano, it allows them to dynamically change where they fly,” noted van Essen.

“Other aircraft were grounded after [the initial eruptions], whereas Hawaiian was allowed to fly because they are equipped with this real-time connectivity and the controllers trusted them to be able to fly around the latest ash cloud based on the information data they had. So, that makes a lot of economical sense to an airline.”

Describing the current state of operational connectivity as “not your Grandmother’s satcom,” Inmarsat vice president safety and operational services Mary McMillan suggested that a new way of thinking about data was in order. She said:

I think as we start to explore the ways that we are going to be able to use connectivity to the benefit not only in cost savings to the airlines, but obviously as we talk about the benefit to society and to our passengers as a whole, that cost benefit analysis actually starts to change.

Inmarsat certainly recognizes that. We know that it’s going to be an important part of that equation, it’s the cost of the equipment and then it’s the cost to operate that equipment. So, we’re actually changing our business models as well to ensure that we are encouraging the use of data. Much like your cell phones, you buy a package where you don’t even think about the data that you’re using anymore because you’re actually using it to benefit you in ways that you never even really imagined a few years ago.”

“This is a market report,” stressed van Essen. “It’s not a clear recipe for an airline, like, this is exactly what you should do [and] different airlines will put different focus on different things. The difference between this report and chapter one is that chapter one was, in a way, easier as a topic to cover because we basically created four buckets and said: ‘OK, these are the different areas where different revenue streams will come from.’ In chapter two, it’s across your whole operation and the wider ecosystem tied into that. So, I would say, generally, there are less big benefits but a lot more smaller benefits that you need to take into account to actually build your business.”

Or, as Dr. Grous put it during his presentation: “Every little thing counts.”

“A lot of processes in the airlines have been defined in the 1960s and 1970s and they have basically stayed like that,” added van Essen. “They’ve been standardized throughout the world and … a lot of that is still based on the technology and capabilities that we had at that time. Now that we have the technology and we can be much more dynamic in real time, what we’re trying to do is encourage the industry to take advantage of that and rethink the way they’re doing things.

“I think that’s quite exciting and I think you’re seeing airlines get on board with that and I think in the end it’s a collaborative effort of the ecosystem. It’s everybody who kind of needs to push in the right direction doing that and then at some point you reach momentum and things start to happen.”

Additional reporting by Mary Kirby

Related Articles:

- Lufthansa Captain’s log shows near 8-year connected EFB effort

- SIA joins airlines seeking to turn biofuel trickle into a flood

- Hawaiian is first up for SB Safety, but Cobham eyes all majors

- Iridium seeks European opportunity to trial NEXT service for ATM

- Will safety service ever transmit over cabin connectivity pipes?

- Press Release: EFB app from SITAONAIR to deliver real-time weather on SB-S

- Thales eyes new comms capabilities for data revolution on flight deck

- Panasonic Global 4D weather offers airline and wider benefits

- Honeywell to launch connected radar application via Global Xpress

- As Boeing forms new avionics unit, where will broadband connectivity fit?

- Press Release: Inmarsat SB-S selected by Hawaiian for A321neos

- Connectivity and data are big drivers for Rockwell after Arinc buy