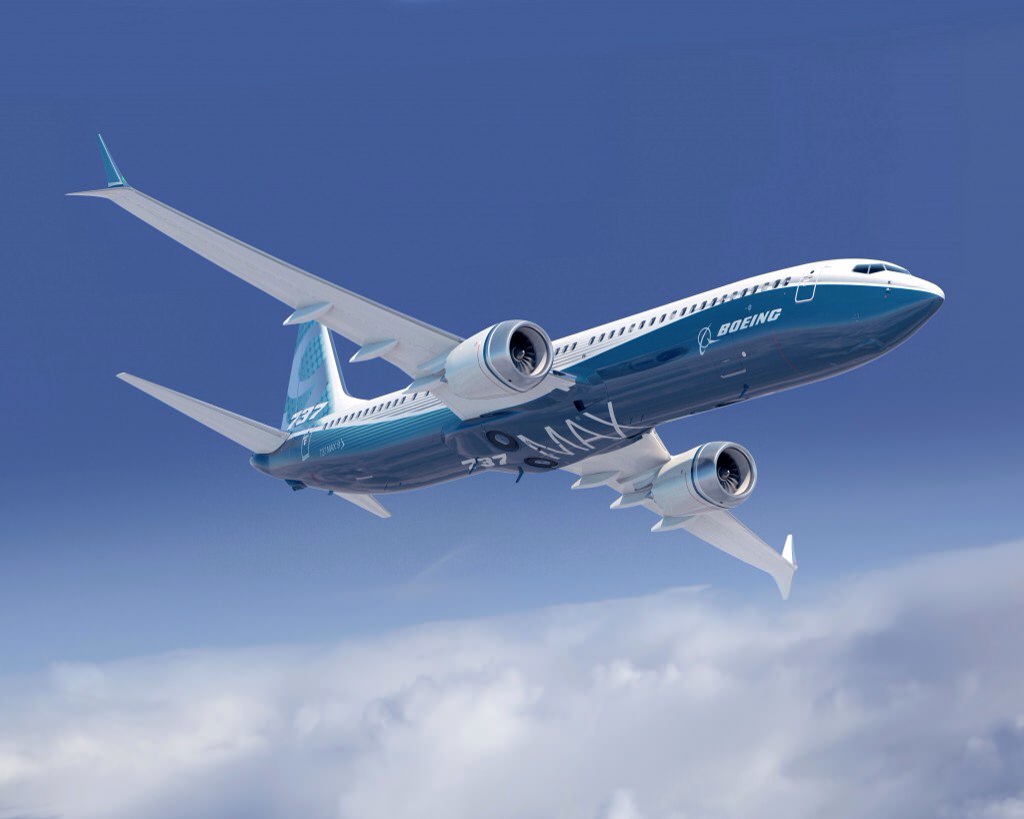

The gap in Boeing’s product line in the middle of the market (MOM) couldn’t have been more noticeable last week at the aviation industry’s biggest showcase, the Farnborough Airshow. Despite mooting a 737 MAX 10, and trying to insist that the 737 MAX 9 will be able to match the Airbus A321neo and its extended range version the A321LR, it was a hard sell for some of the most skilled salespeople in the business.

Airbus certainly took the orders prize at Farnborough this year, with the largest order of the show for 100 A321neo aircraft from AirAsia, as well as a significant conversion of 30 previously ordered Norwegian A320neo family aircraft to the larger, longer range A321neo version with extra fuel tanks, now called the A321LR. Throughout the show, and indeed in all its comments this year, Airbus execs have been delighted in the performance of their 757 replacement.

By contrast, Boeing booked no 737 MAX 9 orders at Farnborough, and it didn’t help Boeing’s media counteroffensive when senior vice president for global sales and marketing John Wojick suggested that the Alaska Airlines-operated 737-900ER Seattle-Miami route couldn’t be operated by an Airbus A321, when American Airlines already does exactly that.

Randy Tinseth, Boeing vice president of marketing, highlighted the scope of this end of the narrowbody requirements. “Five to ten percent of the single aisle market, we believe, over the next twenty years will be in that -700 sized aircraft, 737 MAX 7 marketplace. When you look at the very top of that market, the MAX 9, A321 market, we’re looking at numbers some at twenty and twenty-five percent. That means the center of the single-aisle market, where the MAX 8 and the A320 is, you’re looking at about seventy percent of the market.”

“The heart of that market is the 737 MAX 8, which does extremely well in the marketplace,” Tinseth said, but that isn’t reflected in the orders this year, and airlines seem to be remarkably convinced that there is a fair amount of need.

Indeed, when comparing middle of market to market forecasts, Tinseth said, “We don’t necessarily have the airplane in the forecast. We’ll take a look at that airplane in that market, and then we’ll allocate traffic to it. When you bring in an airplane in a space that’s not being addressed today, it will have a stimulative effect in the market, and it will have some collateral impact up and down both single aisles and widebody markets. That’s the challenge. The fact is, the better airplane you bring to the market the more it’s going to both stimulate traffic as well as impact other marketplaces.”

The problem for Boeing is, much of the market seems to think the A321neo is a better airplane than anything Boeing is offering. Much of the advantage the A321neo holds over the 737 MAX 9 is in terms of thrust to weight ratio. The A321 is simply further off the ground than the 737, which means that it can hang larger, more powerful, and more efficient turbofans off the wing. The best option for the 737 family to compete is, for an aircraft of the -900 or MAX 9’s length, to raise the nosewheel in order to enable an increase in turbofan diameter. Yet, as the fact that Boeing has not done so for the MAX 9 as currently sold demonstrates this is by no means a simple exercise, nor does it provide as many options as the A321.

To an extent, Boeing’s provision of an ultra-high density 200-seater version of the 737 MAX 8 — the Ryanair-launched aircraft currently called the 737 MAX 200 — has affected sales of the MAX 9. Boeing’s Tinseth noted, though, that “the MAX 9 is an airplane with a two-class configuration of 173 seats. When we get to the single-class high density I think it’s about 215 to 220. The MAX 200 is really about unlocking the capabilities of the MAX 8 as a low-cost carrier option for the aircraft. You’ll see 199, 200 passengers on that airplane. It’s really about that single-class, high-density market.”

Despite multiple, restated questions from journalists though, it seemed that Tinseth didn’t really have an answer about the order outperformance of the A321neo over the 737 MAX 9, or the fact that key customers like Norwegian aren’t interested in the proposed MAX 10. His best effort:

Despite multiple, restated questions from journalists though, it seemed that Tinseth didn’t really have an answer about the order outperformance of the A321neo over the 737 MAX 9, or the fact that key customers like Norwegian aren’t interested in the proposed MAX 10. His best effort:

“I’ll go back to the fact that we built this large backlog on the single aisle side, we’re delivering half the airplanes in the market, we continue to deliver half the airplanes in the market, we have a product strategy that’s working, we’ll make adjustments if we see necessary. As I looked at those delivery numbers for the first half of the year, it was a surprise we were able to deliver more airplanes than our competition. I think again as we go out and stabilise around the MAX, and start delivering those, we’ll be able to accelerate our production moving forward. The single-aisle market is a strong market, it continues to be a strong market, and I’ll also say, when you take a look at the models that we see across the board… model makes at time of order can be significantly different than the model mixes that are actually delivered in the marketplace.”

Given the just-proposed 737 MAX 10, and no appearance of the perennially discussed though not yet released next-generation small twinjet for the middle of the market, Airbus’ John Leahy’s jibe about Boeing “the Paper Airplane Company” might be hitting just a little close to home in Seattle at the moment.