UK-based aviation and maritime intelligence provider Valour Consultancy recently made a bold prediction: SpaceX’s Starlink inflight connectivity (IFC) service will secure a 39% share of the connected commercial aviation market by 2034.

“[S]tarlink has brought to market a high-quality IFC service that airlines and business jet fleet operators are glowing with praise for. As such, Valour Consultancy anticipates Starlink will acquire a 39% market share (more than 7,000 aircraft) of the commercial aviation market by 2034,” suggested Valour, noting that the Ku-band Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite operator is “shaking up” the sector with “a high-performance IFC service, a fundamentally distinct go-to-market strategy, and powerful brand presence.”

The consultancy also predicted in reference to Starlink that, “Its growth in the business aviation market will be more gradual, due to a focus on larger aircraft and the highly fragmented nature of the market; however the vendor is still forecast to serve more than 3,000 private jets by 2034.”

Having secured full-fleet equipage deals with Air France, Qatar Airways, SAS, United Airlines and WestJet, in addition to a cluster of smaller airlines, SpaceX’s Starlink has certainly made rapid progress in growing its backlog.

By mid-April 2025, its Starlink Aviation-branded service had been earmarked for over 3,000 aircraft, as SpaceX declared on its stand at the Aircraft Interiors Expo in Hamburg — a figure that is understood to include business jets. Assuming all stated commitments remain in play, SpaceX has already inked deals covering nearly, or perhaps now fully one-third of Valour’s forecasted 10,000 tails by 2034.

Another big win might be in the offing, with Bloomberg reporting that Emirates is in talks with SpaceX to fit its widebody fleet with Starlink (satellite industry consultant Tim Farrar said on X in March that Emirates has already handed a full-fleet IFC equipage deal to Starlink.) Air New Zealand is also currently trialing Starlink with an eye on powering free Wi-Fi on its domestic fleet.

As a rural residential user of Starlink, I understand why airlines are gravitating towards low-latency LEO-based IFC. Offering passengers an at-home connected experience in the sky has become table stakes for premium airlines. And LEO connectivity is indeed snappy.

In my experience with Starlink, after an admittedly rough patch in the beginning, I’ve found that the service consistently delivers download speeds of 180 Mbps or more and sometimes well over 200 Mbps; upload speeds of 14 Mbps or more, and ping times that are often in the lower double digits. According to Ookla, US Starlink Speedtest users in the first quarter of 2025 were able to get speeds consistent with the Federal Communications Commission’s minimum requirement for fixed broadband of 100 Mbps down and 20 Mbps up.

The benefit of a GEO component

But when it comes to choosing inflight connectivity, latency and speed, whilst significant, are not the only factors coloring some airlines’ decision-making. Landing rights and geopolitical considerations, including for airlines that fly into and over Russia and China; capacity around hub airports; a need for formal bandwidth guarantees, as covered by Service Level Agreements; and global maintenance support may also factor into the equation. That’s among the reasons why there’s also material momentum behind multi-orbit IFC solutions including those that enable airlines to exploit the benefits of both LEO and geostationary (GEO) satellites.

For example, Intelsat’s multi-orbit LEO/GEO IFC, with the Ku-band LEO portion powered by Eutelsat OneWeb, is now rolling out and wowing passengers on regional jets operated by Air Canada and American Airlines (and soon Alaska Airlines). Eutelsat OneWeb LEO service is also part of the Hughes Network Systems multi-orbit, multi-band IFC solution coming to Delta Air Lines’ Boeing 717 fleet, and select Airbus A321neos and A350-1000s

Given the talkability around LEO, one could be forgiven for thinking that GEO in aviation and elsewhere is going the way of the dodo bird. But whilst the order pipeline for new GEO satellites has certainly slowed considerably, GEO is “not going away,” ST Engineering iDirect head of mobility business development Chris Insall said as a panelist on the IFC Revolution session moderated by your author at the APEX TECH conference in Los Angeles.

A prominent aero modem manufacturer, ST Engineering iDirect also developed the first ever ground platform for High Throughput Satellites. Viasat (through its Inmarsat acquisition), as well as Intelsat, SES and Eutelsat deliver managed services over the platform, and SES recently inked a fresh MOU to use ST Engineering iDirect’s nextgen virtualized ground network, Intuition, to support multi-orbit MEO/GEO connectivity. “GEOs will stay in service for 15 years,” said Insall, “or with a mission extension, which is what Intelsat have done, way beyond that, with dedicated capacity and dedicated [coverage] areas. And software-defined satellites (SDS) have given much more usability to the capacity that is there already.

“And so, you will see with [Viasat’s] GX 7, 8, 9, and with Intelsat’s SDS constellations — Intelsat stated it’s like a 400% increase in their GEO capacity — it is absolutely not going away. It’ll be there as an option, and where it’s useful and appropriate, like when regulatory [is a factor] or for dedicated service, or for example, streaming… A dedicated GEO bird is very, very useful for that for all kinds of reasons.”

The capability, especially of software-defined GEO satellites, to optimize capacity utilization by deploying resources just where they’re needed will remain especially important around busy airport hubs where there are lots of jets in one location, said Bill Milroy, the chairman and CTO of antenna-maker ThinKom Solutions, whose hardware is part of Hughes’ aforementioned multi-orbit, multi-band IFC offering coming to Delta.

“Most of these LEO constellations are not designed for urban type use,” Milroy noted at APEX TECH. “GEOs are very good at doing that, and combined with perhaps a terrestrial network as well, that might be the better solution” for busy hubs.

“I don’t own a stock in any GEO companies,” he added, “but I think the GEO companies are really upping their game. I don’t think they’re giving away anything in terms of service that’s available, and we’re proud to support GEOs, and continue to do so, and embrace MEOs and LEOs as they come along.” It’s notable that GEO IFC service providers are throwing more capacity than ever before at the aviation market, as pricing has fallen dramatically.

Augmenting GEO with LEO

But how can IFC stakeholders accommodate airlines that want to add the oomph and low-latency snappiness of LEO to support applications like inflight gaming whilst retaining the benefits of their current GEO IFC system?

One option would be to augment an installed GEO satcom solution with a LEO-only electronically steerable antenna (ESA). During the SATELLITE conference and exhibition in March in Washington D.C., Air Canada revealed it is in talks with IFC service providers, including its current provider Intelsat, to understand its options for adding LEO satellite service to the Ku-band GEO satellite-powered 2Ku IFC systems on its mainline fleet. And, in a similar vein, Panasonic Avionics said it could add a LEO-only antenna to aircraft fitted with its legacy gimbaled antenna to facilitate multi-orbit connectivity — even as it brings its own multi-orbit ESA-based IFC offering, inclusive of Eutelsat OneWeb LEO service, to market.

And so, at APEX TECH, RGN asked: does it make sense to slap a LEO-only antenna alongside a traditional GEO-focused antenna?

“Oh, absolutely,” said Mike Moeller, senior vice president, aviation at Quvia, the first AI-powered Quality of Experience (QoE) platform for ships, planes and remote sites. Traditionally, GEO-based IFC-fitted widebodies have not been great over water because GEOs are usually focused on areas where people are located, with the exception of Inmarsat’s GX network (now owned by Viasat). Said Moeller:

If you did add like a LEO to a GEO system for a widebody, now all of a sudden you have all of this capacity over the oceans [via LEO] and now you can make the widebody maybe the best experience in your fleet, because all of the dynamics change just from a standpoint of the orbit.

So yes, I think adding a LEO to a GEO system to augment, that is absolutely a phenomenal idea, specifically in the widebody. Then the question is, who’s routing the traffic? That’s what we like to go do. So I’ll throw a spin in there. We like to route that traffic over the best network and blend those together to go do that.

Another argument can be made in favor of multi-orbit/multi-network LEO/GEO IFC adoption: it provides a level of redundancy in the event of a service anomaly.

Reducing risk?

Last year’s mysterious in-orbit break-up of the Intelsat 33e geostationary satellite — which was preceded four years earlier by the total loss of Intelsat 29e service — and recent outages experienced by LEO network operators bring into stark relief the value of multi-orbit and multi-constellation connectivity solutions.

And what of geopolitical unpredictability? Weird stuff happens. Allegiances and indeed brand equity can change very quickly.

EPFD wild card

There are also some open questions around whether or not the United Nations’ International Telecommunications Union (ITU) will relax the regulatory requirements governing Equivalent Power Flux-Density (EPFD) limits, which have been in play since 2000, protecting satellites in geostationary orbit from interference from non-geostationary satellite orbit (NGSO) systems.

Last year, in a petition to the FCC for a review of the spectrum sharing regime, SpaceX argued that the existing rules governing EPFD unnecessarily restrict the operations of NGSO systems. “For example, today’s EPFD limits require NGSO systems to artificially limit their radio frequency power, namely effective isotropic radiated power (EIRP), needlessly reducing signal quality on the ground and making it more difficult to ensure a consistently high level of service,” SpaceX argued (pdf).

EPFD limits, SpaceX further noted, can also require NGSO systems to implement large “avoidance angles” away from the arc of geostationary satellites around the equator to prevent in-line interference events with geostationary satellites, restricting the use of any satellite that appears within the geostationary satellite avoidance angle with respect to a ground location.

Though SpaceX has managed to grow in aviation without blanket changes to the framework, a relaxation of EPFD limits would, among other things, enable it to enhance signal strength to improve reliability and speeds, and dramatically increase capacity, greatly benefitting the verticals it serves.

Though Viasat and EchoStar opposed SpaceX’s petition, the FCC in a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) adopted on 28 April 2025, and published by the Federal Register on 13 June (triggering a 45-day comment period), said it is initiating a review of the “decades-old” spectrum sharing regime between geostationary and NGSO systems operating in the 10.7-12.7, 17.3-18.6, and 19.7-20.2 GHz bands.

The FCC’s wording in the NPRM certainly seems to suggest that decisions favorable to NGSO are afoot, noting that its goal is to do “everything possible to clear the way for American innovation and investment in space excellence” and that it will keep this goal at the forefront.

“By taking a fresh look at today’s satellite technology and operations, this proceeding will ensure highly efficient and effective use of the shared spectrum, and support a more efficient and competitive market for satellite broadband and other in-demand services while uncapping the potential of satellite constellations that were unthinkable when the current regime was developed, to the ultimate benefit of American consumers,” it said in the NPRM.

Should the FCC ultimately favor a new framework, it is not necessarily guaranteed that the ITU will follow in lock step, as noted by ThinKom’s Milroy at APEX TECH.

Stressing that the firm “likes all constellations including Starlink and likes all consulting groups including Valour,” of which it is a customer, Milroy said that whilst the FCC’s NPRM is percolating now, the issue may not be addressed internationally “until either the next work (WRC-27) or the work after that. And in the geopolitical environment, maybe it used to be that the ITU used to say, ‘oh, whatever the FCC is thinking is correct.’ Not sure we’re really there,” he said, adding that Valour Consultancy’s forecast about Starlink is “also predicated on the V2 satellites, which are predicated on Starship getting its legs under it and being able to launch those satellites, and the relaxation of EPFD and what goes along [with that].”

“So there’s a lot of ‘ifs’ in there,” he said. “And [Amazon’s Project] Kuiper is launching very quickly. OneWeb is already up there and probably doing a little bit of a replenishment. So, our point is, we love all of those, but as a customer and making a decision, and perhaps signing a contract with someone — or committing/pseudo signing a contract by putting that proprietary equipment on your aircraft, which is sort of like signing a contract — it could be wrong. There’s uncertainty. The geopolitical environment could change.”

Staying flexible

Valour Consultancy, meanwhile, reckons Amazon’s Project Kuiper is “the main threat to Starlink dominance” once it enters the market.

Amazon certainly intends to make a compelling direct offer to airlines. Just as it has helped airlines transform their digital operations on the ground via cloud infrastructure market leader AWS, the tech giant could leverage those relationships and pipe Amazon Prime and Audible over Project Kuiper Ka-band LEO satellites, including to aircraft seatbacks. Picture, for example, an airline’s branding wrapped around an Amazon Prime inflight experience, a bring-your-own-license model for IFE. That’s seen as a very easy scenario to accommodate.

Amazon has successfully launched its first tranche of 27 satellites; it will launch its second batch of satellites on 16 June via United Launch Alliance’s Atlas V rocket, pending acceptable weather. Even so, Project Kuiper’s entry to the aero market appears to be a few years off.

However the market shakes out, and indeed whatever new satcom options arrive, flexibility should be the name of the game, Quvia’s Moeller urged.

“I always used to say, and Bill Milroy kind of talked about it, not to fear the future, but to embrace it. Here comes Kuiper, here comes Telesat [Lightspeed], here comes… other parts of the world; the Chinese that launch a satellite [constellation], or other. We’re not just thinking about North America. This is a global system now that has to go in different regions of the world,” he said.

“Knowing that the world is changing every day, much less, passengers are changing and technology is changing — that flexibility, I think, is what the airlines are demanding.”

Related Articles:

- Air New Zealand commences trial of Starlink inflight Wi-Fi

- Royal Brunei taps Intelsat multi-orbit IFC for A320neo fleet

- Quvia sees aero following cruise with multiple connectivity providers

- JetBlue observes fundamental change in passenger behavior

- Viasat details Amara nextgen inflight connectivity strategy

- Panasonic, Airbus discuss possible interim solution for Ku HBCplus

- Intelsat linefit and SB wins see multi-orbit IFC come to E2, 787

- Discover Airlines pivots from GEO to LEO/GEO with Panasonic on A330s

- Airbus adds Amazon, confirms Hughes, removes Viasat GX from HBCplus

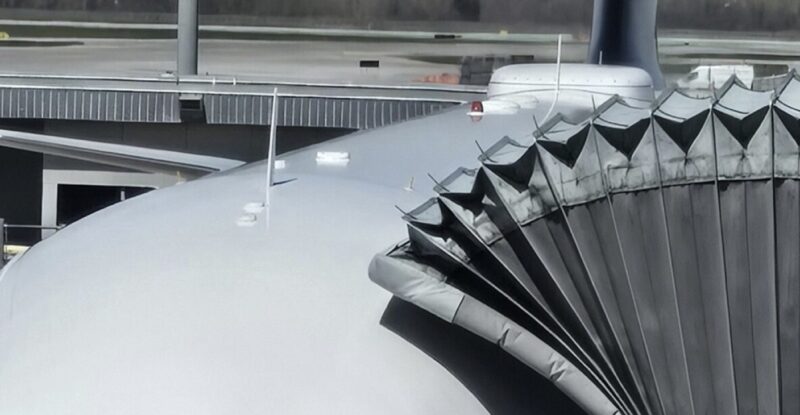

Featured image credited to Becca Alkema