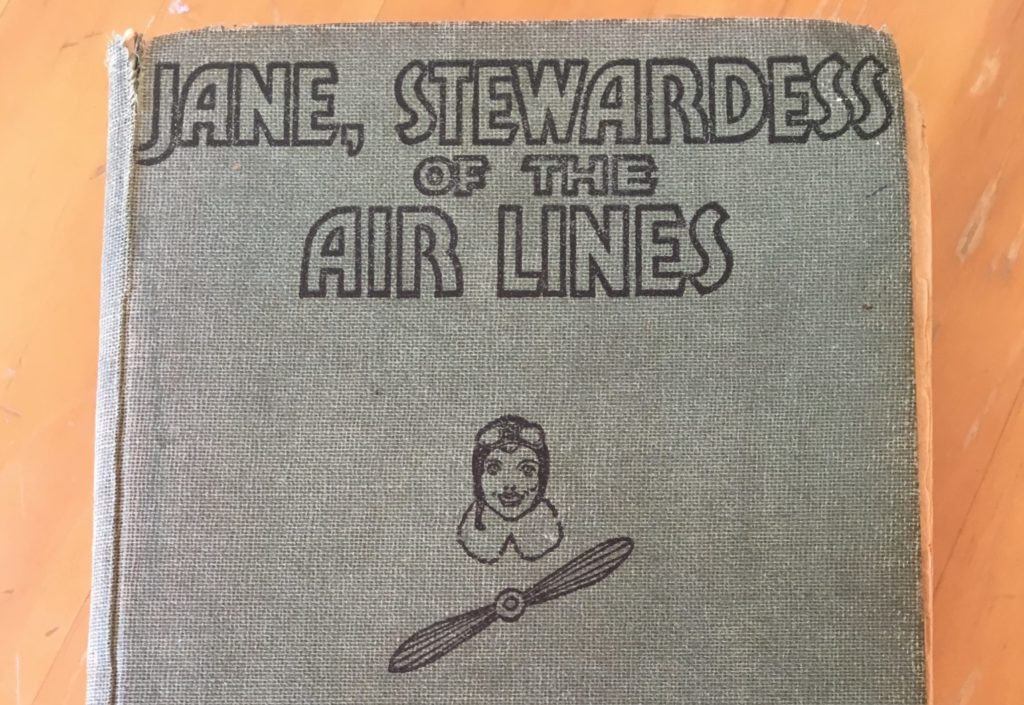

Browsing through a selection of vintage books at my favorite thrift shop on the Outer Banks, I laid hands on a tattered little treasure published in 1934, entitled Jane, Stewardess of Air Lines by Ruthe S. Wheeler. It tells the fictional story of a young nursing school graduate who is offered the opportunity to take flight.

“We have come to the conclusion that the addition of a stewardess to our flying crews is essential and at present we are contracting young women who might be interested in this work,” read a letter from the manager of Federated Airways. “Our first requirement is that the prospective stewardess be a graduate nurse.”

Plucky Jane Cameron responded, “It’s a real chance to get into a new field for girls. Air travel is developing rapidly and perhaps we can grow with it.”

The 246-page story follows Jane through her first year as she tends to passengers, learns to fly, gets her license and becomes a stunt pilot.

A later book, Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants offered up a review of Wheeler’s work, saying: “Steel-nerved Jane was merely one heroine in a broader genre of air crime and aviation dramas popular with American readers in the 1930s. But few authors after Wheeler would create a stewardess character of such crisis-tested bravery or one whose technological mastery of flying rivaled, even exceeded, that of male pilots, the usual subject of aviation hero worship.”

Over the past several years, I have encountered modern-day versions of Jane, who have been profiled on this site. Many share Jane’s sense of adventure. But all of these exceptional women share common traits of ambition, quiet confidence and an impressive work ethic.

Take Helen McNamara, a pilot who began her career with British Airways in 1998 when she was accepted into a scholarship program. She began flying two years later. She is one of 250 women, or about 6% of the pilots, who fly for BA.

“I was backpacking around Africa when I became friends with some bush pilots,” McNamara said. “They took me flying and as soon as I was up in the air, I realized that was what I wanted to do – become a pilot.”

Ghada Mohamed Al Rousi remembers the thrill that came from riding a roller coaster as a small child. At the time, she had never given a thought to becoming a pilot, but once she set foot in a cockpit a few years ago, the thrill was back.

“When I first entered the cockpit I just felt ‘I can do it’,” said Al Rousi, an Emirati who is a First Officer with Air Arabia. “Wanting to become a pilot was a feeling I didn’t necessarily feel when I was younger. It came a few years ago. But as soon as I felt that way it was always in my mind that I wanted to do a pilot training course.”

One of my favorite interviews was with Colleen Barrett, President emeritus of Southwest Airlines. Working in partnership with founder Herb Kelleher, Barrett shares credit for the success of the airline that started flying in Texas in 1971. Barrett was instrumental in establishing a culture where she preached the gospel of servant leadership throughout her career. Women comprise some 40% of the Southwest work force.

“I was born to be a servant leader,” she said. “You can’t do things to get accolades; you do things because they are the right thing to do.” In 2016, Barrett received the prestigious Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy for her contribution of “enduring value” to the US aviation industry.

I’m always impressed with the real-life women who have followed in Jane Cameron’s fictional footsteps, following an uncharted path. They’ve moved from the galley into the cockpits, the executive offices and the boardrooms. They continue to make all of us proud, and hopeful for the future.

Related Articles:

- Melissa Myers: Experiencing my first flight in a small plane

- Air Arabia pilot champions careers in aviation for women

- Passion for flight propels BA woman pilot

- Colleen Barrett talks Herb, go-go boots and service with a smile

- Pilots Fly It Forward to inspire new generation of women aviators

Featured image credited to istock.com/MichaelWarrenPix