In part one of our Lean Into Aviation profile of pioneering Rockwell Collins human factors & systems engineer Laura Smith-Velazquez, the Mars One semi-finalist discussed how her staunchly matriarchal Cherokee upbringing shaped her education and career aspirations from an early age.

Following up on her previous statement that steering girls and young women toward STEM fields is only half the battle, Smith-Velazquez opens up again for RGN about her personal experiences as a woman in a primarily male-driven profession and how her potential one-way ticket to Mars could change her life forever.

“It has been my experience in engineering that often I am the only female on the team,” says Laura Smith-Velazquez. “I rarely work with other women and I have worked at major companies such as Northrop Grumman, Textron Systems, and Lockheed Martin. But when I do, I have found that they are like me and do not have children and generally they are often not in a role of authority. If they have authority they are program managers, not tech leads. When women I work with do have children, they have generally stopped their career, had children, and then restarted or had a stay-at-home husband, which is still rare. A lot don’t ever come back to their careers. It’s [just] too expensive to have day care so parents often have to choose who must stay home.”

Though the mother is often the one to do so, Smith-Velazquez says fathers who stay home or go part-time to help with the family can also find their careers stymied by the decision. “Our corporate resources are just not geared to supporting careered families and neither is our economy. So, someone has to take the hit.”

And as far as acceptance of female engineers in the traditionally male-driven aviation/aerospace tech sector goes, Smith-Velazquez says things are changing, but the old boys network still rules the roost.

“When I started engineering it used to be that you took on masculine characteristics to survive in the workplace, [for instance] Teresa became Terry. I was even once told to wear a turtleneck because guys just weren’t sure how to act around women appropriately, especially a young attractive female. Now I think we are ‘allowed’ to be women to a certain point. We still are required to have, to quote Hermione from Harry Potter: ‘the emotional capacity of a teaspoon’ and hide our emotions, but we get to dress like women now.” That said, Smith-Velazquez freely admits to quitting jobs where she knew she would never advance because being a woman made her team members question her expertise and credibility.

“One of my friends was interviewing for a job at my workplace and our chief engineer, who was interviewing her … asked me how old she was and if she could work with a women of authority because: ‘You know how women can be with each other.’ I was shocked. I have had to be forceful in getting one company to deal with harassment since it was their customer and I was a contractor. That shouldn’t matter, but it does. It is a fact of every day life in STEM fields.”

Smith-Velazquez suggests that even in companies with good corporate cultures, women tend to advance less, and if they do, there are still many double standards. “Amusingly enough, letting my hair go grey was seen by most women in my field as a dead career move,” says Smith-Velazquez. “If men are older, they are wiser, if women are older, they are used up and done. [It’s] crazy, but multiple women told me that it would be limiting my career advancement, but, I chose to let it go grey anyway. That’s just one double standard that we still deal with in the workplace. Another one I hear often [is that] men with families are ‘more stable’ while women with families ‘are a liability as they will put their families first’. In many instances my managers don’t even know they’re doing it.”

Laura Smith Velazque was told she would be limiting her career advancement by going grey.

Thinking back on her career, she continues, “I’ve had performance reviews which focus on how I am perceived in my interactions not on my actual performance results and often I have been compared to my male coworkers specifically. In addition I’ve even been given a 2 (below average) on my performance, even though I had achieved 4 (above average) on my goals. One 360/270 I did with my manager was enlightening as he rated me 2 points below everyone, even the coworkers I had problems working with. It was very revealing for both of us and amazingly enough, he too took a step back and took a good look at himself and how he was rating his only female engineer. I respected him greatly for keeping an open mind and doing so.”

And though Smith-Velazquez says that her younger male co-workers do seem to be more open to working alongside women and she has seen men in the industry starting to champion female engineers unasked, she admits that: “We still have a long way to go.”

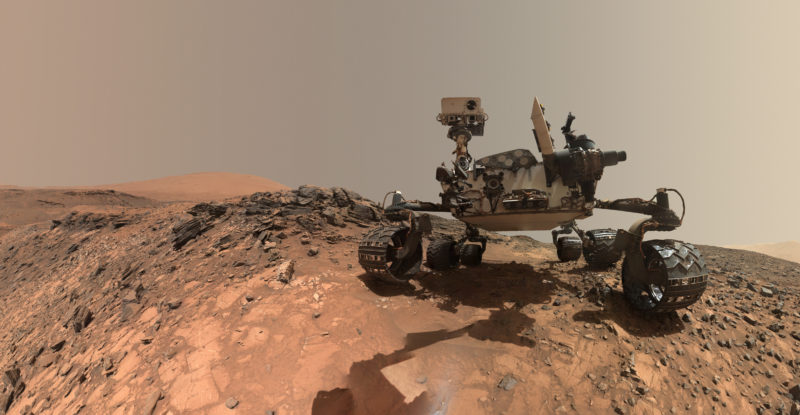

And speaking of long ways to go, the greatest divide facing Smith-Velazquez right now has more to do with bridging vast distances of time and space than overcoming stereotypes in the workplace. Especially since she became one of the 100 semi-finalists last year for the groundbreaking, if somewhat controversial, Mars One project.

Launched in 2012 in the Netherlands by entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp and pioneering engineer Arno Wielders the Mars One project is hoping to establish a permanent human colony on Mars by 2024. And though the project’s technical and financial feasibility has been criticized recently in some circles, Smith-Velazquez says Lansdorp and Wielders’ bold vision for Mars One hooked her from the get-go. She says:

Mars One is about a vision to implement a permanent human settlement on Mars. However, to me, it’s more than just about a settlement. It’s really about the advancement of the human race, exceeding our grasp, being daring, and providing motivation to achieve what people think is impossible. It’s about giving hope and creating excitement about the space program, about evolving to that next level and [getting] us out of our thinking about the world in terms of us as individuals or a single government, but us as a planet, striving and working together for a common goal, using all of our diversity and ingenuity to do so. It isn’t about the US going to Mars, or Europe going to Mars, this is about the people of the Earth going to Mars. I’ve never seen anything so without boundaries, encompassing diversity, that could unite us a planet. It’s quite the vision and I’m excited to be a part of that.”

And though some might think twice about embarking on a one-way trip to Mars, Smith-Velazquez says she and her husband (who also applied for the project but didn’t make it to the semi-finals) had no such qualms. “My husband actually heard about [Mars One] first,” she says. “When I came home from work he asked me: ‘So, you want to go to Mars and never come back?’ My response was: ‘Sure!'”

“The reason it’s a one-way trip is mainly a logistics problem,” admits Smith-Velazquez. “We just can’t afford to launch the amount of fuel, food, and equipment it would take to sustain a round trip mission. In addition, you would need a particular vehicle to bring it all with you that could land on another planet and launch itself again. However, if you assume you are not coming back, the logistical problem becomes much simpler since you need way less resources. If we can figure out how to use the technology we have today to sustain a habitat — which NASA has already done a lot of research on – then it makes a mission much more realistic, if more daring.”

“Probably the most difficult aspect is leaving everyone behind knowing you will only be able to e-mail or send videos to your loved ones. Also, knowing that if anything happens, there is no way out. You are there to stay so you need to be resourceful, tenacious, resilient, and work together to survive. There is support from Earth, but it takes a long time to get to you if you need supplies, and communication is not in real-time.”

And though the next step in the process will be a lengthy one – Smith-Velazquez says Mars One has encouraged the 100 semi-finalists to group themselves into smaller groups of 10 in order to get to know one another before the next down select, which is still a couple of years off – Smith-Velazquez admits that she is ready for anything. Even if that means she might never share the same planet with her husband, family and friends again.

“I have wanted to be an astronaut forever. [So], my family was not surprised. The common joke is that I was born past cloud 9 [and] my Dad said that when he heard I was selected, he was so proud he cried,” says Smith-Velazquez. “Obviously my husband was on board right away as he applied as well. In the beginning we figured that since so many people applied, chances were slim that we would get selected, [but] when I got past the first round and he didn’t, we decided to see how far I would go. When I became part of the 100 it became real. We had a very long, heartfelt talk, both with tears in our eyes, about our hopes and dreams for the future. I won’t ever forget the words he said to me: ‘I married you to love and support you, what kind of a husband would I be if I didn’t help you reach your dreams just because I don’t want to be alone.’ He is amazing!”

And though Smith-Velazquez says she and her husband are both well aware that the road ahead is uncertain and that, like many astronaut candidates, she might never go, or ever come back, from even a short mission for that matter, they have chosen to live for today.

“We decided … not to worry about what may or may not happen, but to work towards the goal of making my dreams come true,” says Smith-Velazquez, echoing the drive and determination passed down to her as a young girl from her mother and grandmother before her. “These decision have been some of the hardest I’ve ever had to make. I have a war of two loves, that for my soul mate and husband, and that for my explorer heart who dreams of exploring the stars. How do you reconcile them? How do you choose? I think you never know for sure until you have to take that final step. [And] in the end, he and my family will be with me every step of the way.”

Read part one of our profile of Laura Smith-Velazquez here.